Five Blocks AIQ: Tracking & Analysis of AI-powered Search

Five Blocks AIQ: Tracking & Analysis of AI-powered Search

In the real world, if you want to know what important stakeholders think, you can poll them and analyze how they answer various questions to help you understand what they are thinking. You can then plan strategy accordingly.

With AI models like ChatGPT, Copilot, Gemini, and AI Overviews set to become major influencers of what people think about brands and executives, you need to understand what these AI models are thinking and saying about them.

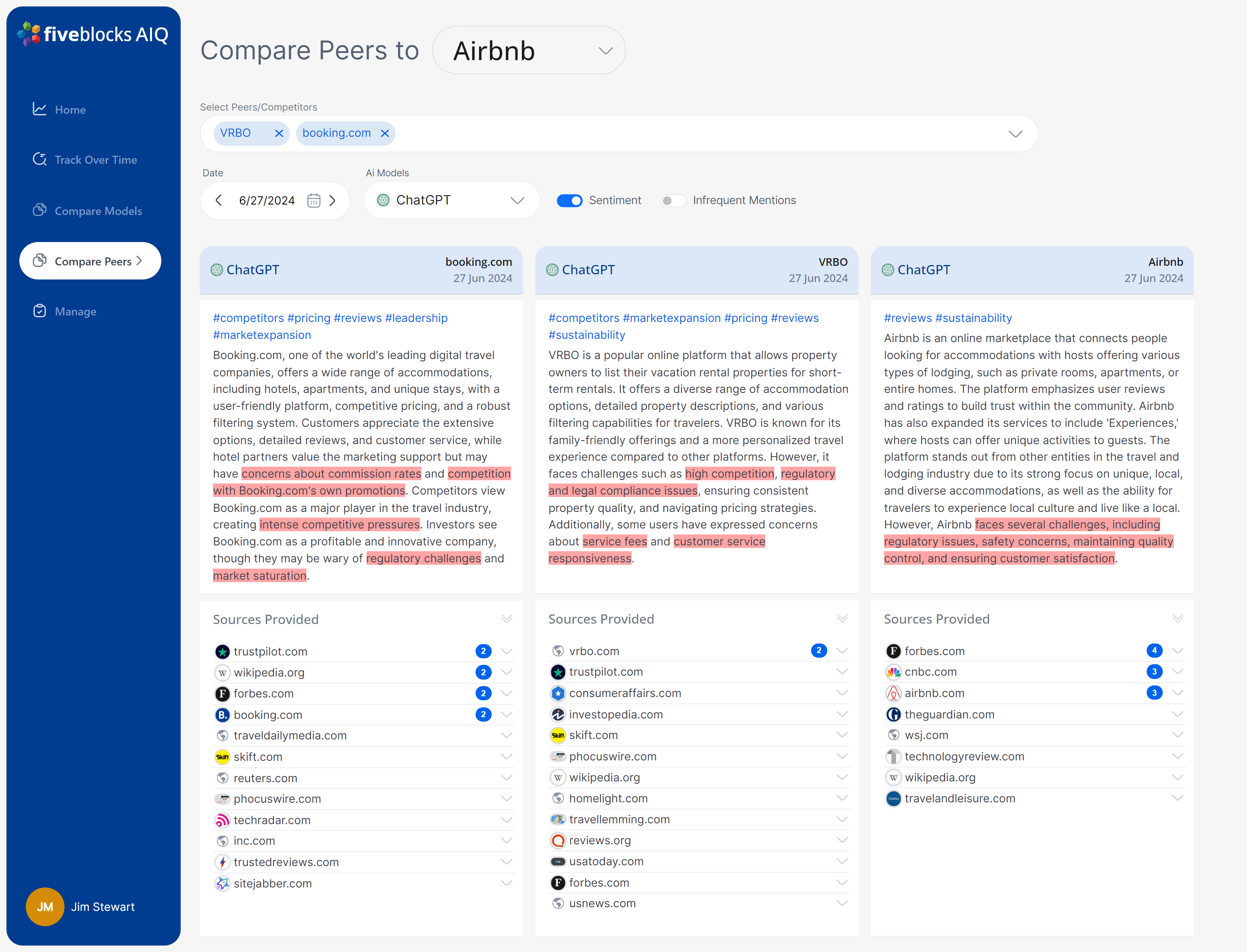

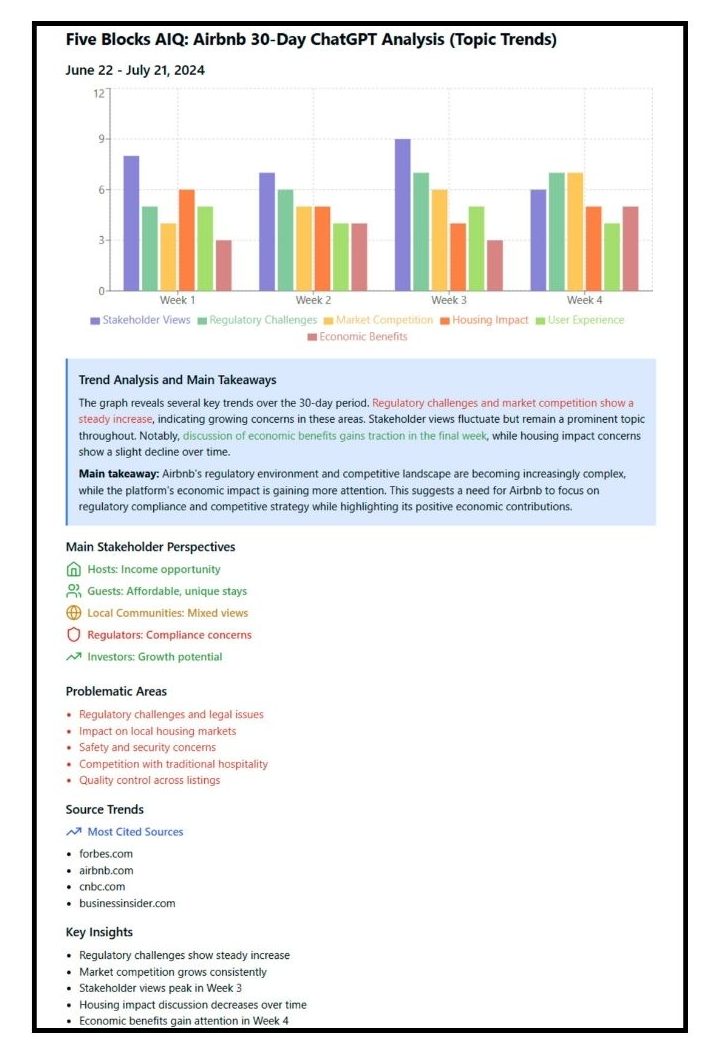

Introducing Five Blocks AIQ, our proprietary AI tracking and analysis platform designed to help you monitor and analyze how leading AI models perceive your brand, based on both LLM training and content available across the internet.

- AIQ gives you a summary of what each AI model “thinks” about your brand.

- It identifies topics and sources that each AI is prioritizing.

- It shows you potentially negative content.

- Most importantly, AIQ gives you context, by comparing your results to those of peers – over time, and across AI models.

- This data analysis is already helping users identify patterns and solutions to reputation challenges.

Using further AI analysis, this platform enables us to create summary reports which can help Brand, PR, and Communications teams focus their efforts.

The future of Search is AI-driven, and AIQ is an essential tool for navigating the complexities of AI-powered Search, and maintaining an accurate, positive digital presence.

We plan to help our clients stay ahead of the curve with AIQ by ensuring your brand is effectively represented in the answers AI provides.

Contact us to learn how AIQ can benefit your brand.

AIQ Features:

- Queries popular AI Models to understand what they think about a specific brand or individual, for example Nabisco or Elon Musk.

- Can also be used to track topics like How is Fedex as an employer? Or: Is MSFT a good investment?

- Highlights unfavorable content appearing in the AI models’ responses, making it easier to identify potential issues without manually sifting through the data.

- AI responses are collated, summarized, and automatically processed to highlight negative content returned by the AI models – calling attention to the most important issues.

- Offers daily tracking – enabling clients to see how recent news may be impacting AI results.

- Offers analysis over the longer term, including the keywords/topics that are trending within the AI responses for a brand.

- Peer analysis provides valuable insights as to the way other similar entities are being treated by AIs. Often this is key to understanding how a brand could potentially be seen.

- Designed to continually track and analyze the way brands are being seen by AI as the technology develops further.

- Will provide specific insights and recommendations on how to address issues and seize opportunities within AI-powered Search.

Navigating Wikipedia: A Basic Guide for PR Professionals

It happens all the time: We are consulted by PR firms with the question: Why is a certain request for a Wikipedia article consistently rejected by the editor community? One firm told us, in exasperation: “Our client is a noted professional in her field. She has 30,000 followers on social media. She has appeared on television a few times. Her results, for credibility reasons, should surely include Wikipedia. Why is relative fame not enough for Wikipedia? What on earth does it take?”

Great question! Here is our answer.

Wikipedia Land, located at the top of the information stream, is hard to navigate without a map. Many great PR teams get lost there, and could potentially save themselves much time and trouble by better understanding the routes the experts take. (See here for more on editing Wikipedia.)

Here are some notes, compiled from the advice of some of my colleagues, who are experienced trekkers.

- Notability is the gold standard for a page on Wikipedia (see why this is, below.) This is not the same as being well-known. Having a podcast, or appearing as an expert on TV, can sometimes help with Twitter verification; but they are not sufficient for Wikipedia. The theoretical bar for notability in Wikipedia generally amounts to something like: If we were writing a big encyclopedia for a time capsule, this person or entity would need to be included.

- Since this is so hard to prove, the gateway becomes sourcing. Notability on Wikipedia is determined by legitimate sources, as follows:

- Sources need to be independent (i.e.: not the company’s own website, self-published corporate history, or a press release) and from a reputable, non-tabloid-type source (eg: The Wall Street Journal works great, but The Daily Mail won’t fly.) You generally need three or more of these to help you to get over the notability hump – but there is no exact formula here.

- The sources you cite need to be largely ABOUT the individual or company in question. Sources that mention the entity in passing (e.g. your client is mentioned in a list of top twenty women in education) will generally not do the trick.

- Wikipedia doesn’t accept content that is generated or spoken by the subject of the article for most purposes. However – there are exceptions to this rule, namely, uncontroversial, easily provable statements that the subject makes about themselves (e.g. “Born and raised in Topeka, Kansas.”). Interviews are often not regarded as a good source for most claims, unless the journalist makes independent observations that support the assertion made in the Wiki article.

- On a related note, there is a separate issue of verifiability: The sources you use should expressly support the claims you make on the page as everything written on the page needs to be backed up by legitimate sources. For example, if you are a well-known pediatrician, and are extensively quoted in articles about a nutritional health crisis, these sources would still not be useful to support a statement such as “Dr. X is 55 years old and a graduate of Duke Medical School,” unless this is mentioned in the article. In other words, the source must support the information you want to present in a direct way.

PR teams working to secure press for clients obviously have several goals in mind, but if getting clients to the point of Wikipedia notability is one of these goals, aim for multiple, independent sources that are reliable; intellectually independent of each other; independent of the subject; largely about the subject of the article; and which speak to the statement made (or which the client wishes to make) on the Wikipedia page.

So, for an archaeologist, an article in the New York Times about their innovative method of determining the age of artifacts would ideally be complemented by a trade journal article talking about recent discoveries, and a career highlights profile in a local magazine from their proud hometown, which would cover some biographical facts they wish to have on the page.

By the way, we know many people have flouted these rules in the past! But editors will eventually catch up to those old pages that went up in a shoddy way, and they can get flagged and suddenly taken down. Don’t look at Wikipedia articles created a decade ago and ask why that person got away with less; it is a brave new world, and these rules are much more strictly enforced now.

A few more notes:

- Language on Wikipedia can never be promotional or sound like it was written by a marketing team. A company can be an “industry leader” if that is borne out by a source, but “America’s best-loved brand” type-language would not pass muster. A company’s mission statement belongs in a section describing its marketing efforts.

- Images need to be copyright free – since the rules of Wikipedia state that anyone surfing the internet can use the image. It is essential that whoever holds the copyright has released their rights to compensation for re-use on Wikipedia and elsewhere on the internet. (There are different types of licenses with different limitations and requirements, for instance, to mention the photographer’s name, or to not be able to change the photo in some way, but the crux of the matter is giving up the main copyright for compensation in order to reuse.) There are exceptions to this, most importantly regarding logos. A company’s logo can be used in a Wikipedia article without the company relinquishing copyright. This is justified based on a fair use rationale – the company still owns the copyright, but the logo may be used on Wikipedia anyway.

If you find yourself challenged by these rules, you are not alone. Even future Nobel Prize winners are not spared this indignity! We explored the notability guidelines, and their sometimes curious effect of barring truly notable individuals from the door, in this article about the physicist Donna Strickland.

Of course, if you are having trouble traversing this strange landscape, you can always turn to us, your trusty guides, for advice and direction.

Executives: How to SPF (Search Protection Factor) Your Summer

“Wear sunscreen.”

This iconic advice (given by a “commencement speaker” in Baz Luhrmann’s song from the late 90’s) has become code for the following wisdom:

Life is complicated in unexpected ways, but there are some simple, basic things you can do to avoid an unnecessary crisis. At least that.

This summer, you’ll wear sunscreen to protect your health and your youth – but what (or who) is protecting your digital reputation?

As you Instagram your way through the islands, blog a path through the whiskey bars of Europe, or get tagged by your friends at so-and-so’s pool party, what movement will be taking place on that great portal to your reputation we call Google? Who would you like to be seen as? Who would you like to be seen with? These things are far more in your control than you might think.

Since your reputation is at least as valuable to you as the luggage you insure before your flight, we’d like to state a few (perhaps obvious) tips before your vacation becomes a liability:

- Twitter: If you tweet frequently, your Twitter feed (and, if you are a superstar, the tweets themselves) are likely to rank on Google page one, especially if your tweets are your original content. Make sure the things you tweet are not just fit for your followers on that medium, but for everyone who may be searching for you on Google.

- Images: You may want to change your Facebook profile picture to the new one of you with the great tan and six pack (and also beer), imagining that only your friends will see it. Keep in mind, though, that your profile pictures will tend to rank in a Google search of your name, or your company’s. Which of your “assets” should your investors and board members see?

- Video: Google often provides searchers with a “video carousel” placed within organic search results, if a relevant video is available. Make sure the videos which will appear when searching your name (usually based on the title in YouTube or on your blog) remain professional and relevant.

- Your blog: It’s great if you have one, since ownership (sites where you control or at least influence the content) is one way to strengthen digital reputation. Sites like these will often rank prominently in searches for your name. Are you posting responsible, relevant written and video material on the road? Are you being true to the brand you’ve created for yourself? Remember that reputation doesn’t take a vacation, and often sticks around even longer than the sand everywhere.

- Wikipedia: Do you have a Wikipedia page? If so, you know that this page will appear at the top in search results for your name. And you probably have better things to do on your vacation than track whether any of that platform’s 200,000 editors have made any updates without your knowledge. Luckily, the Five Blocks WikiAlerts tool sends real time alerts to your email whenever there’s a change, so you can know before the Chairman does.

- Google Alerts: Along these lines, we assume you will have already set up a Google Alert for your name and your company’s; if you haven’t yet — this would be the perfect time. That way, you can get to the business of vacationing and just check your inbox periodically to see if you may have an issue. Forewarned is forearmed. Make sure that when you get away from your desk this summer your reputation stays right where you left it. Have fun!

How Deep is Google’s Love?: Where the In-Depth Articles have Gone (and What it Means for You)

Recently, Google appears to have made a significant change to its search results page that eliminated several in-depth articles for many clients. We’ve taken a deeper dive into this development to see what it could mean for brands and high-profile individuals, and the PR professionals who work with them.

As you know, when searching for a brand or an individual, the Google search results page presents a variety of relevant content pieces and types of media to satisfy the query. Often this means a company’s own webpage will appear at the top, followed by third-party content such as Wikipedia and news sources. There may also be social media results (if an individual or brand actively maintains these platforms), along with image results or video content.

Several years ago, Google introduced a section within top search results they called “in-depth articles”. These results looked very similar to other search results, but came from longform media outlets like Variety, Rolling Stone, or The New York Times Magazine. Often, they were a seminal article about the brand in question – articles that may have been placed by their PR teams.

Including these articles on the top results page seems to have been Google’s way of ensuring that a greater variety (and deeper) content would appear in this prime spot. Their inclusion, and the actual articles that appeared within that section, were governed by a different set of algorithms than most search results.

Recently, this section disappeared from all search pages for brands and executives. This happened without any announcement or acknowledgment on the part of Google. It is important to note that in-depth articles for many brands and individuals contained negative content. At the same time, it was the place where particularly engaging longform journalism made its way onto the prime real estate of Google page 1 for a brand.

The ramifications of Google’s elimination of this section are yet to be seen, and their motivation can only be assumed to be “less intervention” following high profile criticism of potential bias in their algorithms.

A whole host of interesting questions arise from Google’s move: What is the corporate (and civic) responsibility of those who hold the world’s data in their hands? Are there cases for intervention? Who decides what those are?

It is interesting to note that alongside this mysterious disappearance, a recent Five Blocks study of CEO search results found there are far fewer news sites (sites such as CNN, CNBC, and others) on the first couple of pages of searches for a CEO compared to a year ago. In addition, those pages feature many more profile sites, where one would find more dry facts (often created by the brand), and less news.

This marked difference in the presence of news within the organic results over the course of the past year, alongside the recent removal of the in-depth article section, means that page 1 of search for brands and individuals will contain far more“owned” content – i.e.: information they control.

For some brands this would appear to be a positive turn of events, but for many this trend means they will not automatically have great media pieces (which they often earned by being genuinely great) appear prominently in searches. It means they will need to work harder to deliberately ensure that the best third-party media does in fact place highly within their profile. Savvy communications teams will find ways to enhance their brands’ online presence within these brave new parameters.

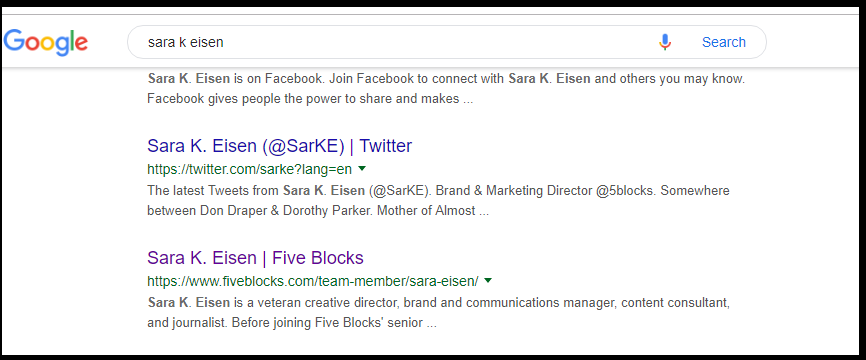

— Sam Michelson, with Sara K. Eisen