The Day LinkedIn Disappeared from Google

On May 6th, overnight, about 273,000,000 LinkedIn results disappeared from Google search results.

We noticed it first, or rather – our technology did.

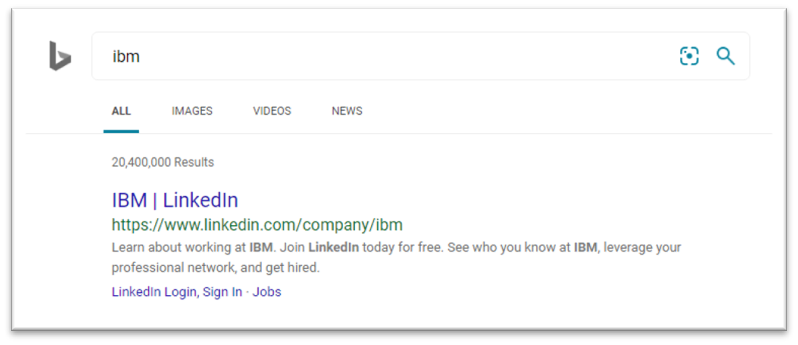

The below screenshot from our IMPACT analytics platform shows that LinkedIn typically appears on page 1 for “IBM,” but on May 6th — it disappeared completely.

It was the same for individuals. Search results for “Mary Barra” (CEO of GM) showed that although she usually has LinkedIn as the first result after Wikipedia and her corporate bio page, on May 6th it was gone (replaced by a second link to GM’s site).

At the same time that LinkedIn disappeared from search results, the icon for LinkedIn also disappeared from the Knowledge Panel. For IBM it was replaced by a Pinterest icon. See before and after..

The LinkedIn disappearance was across the board.

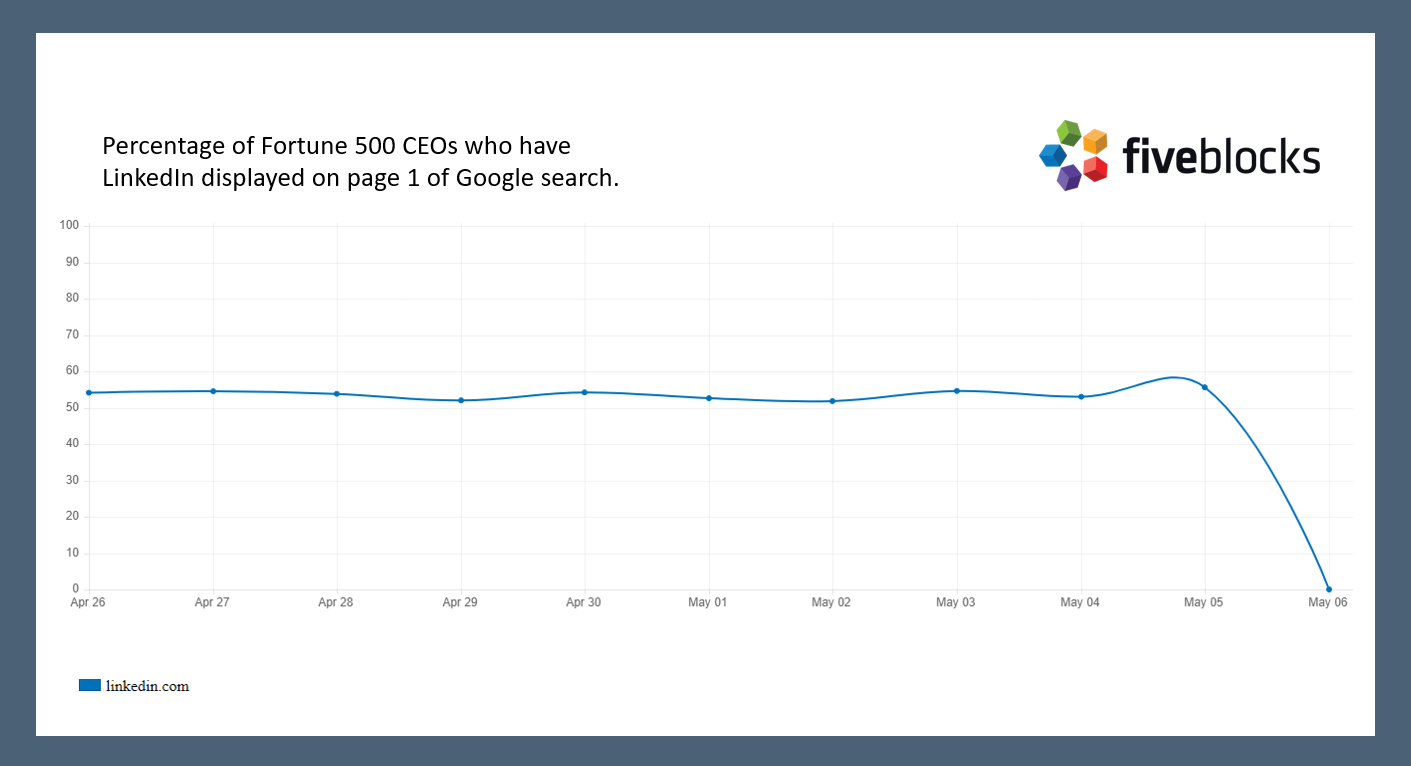

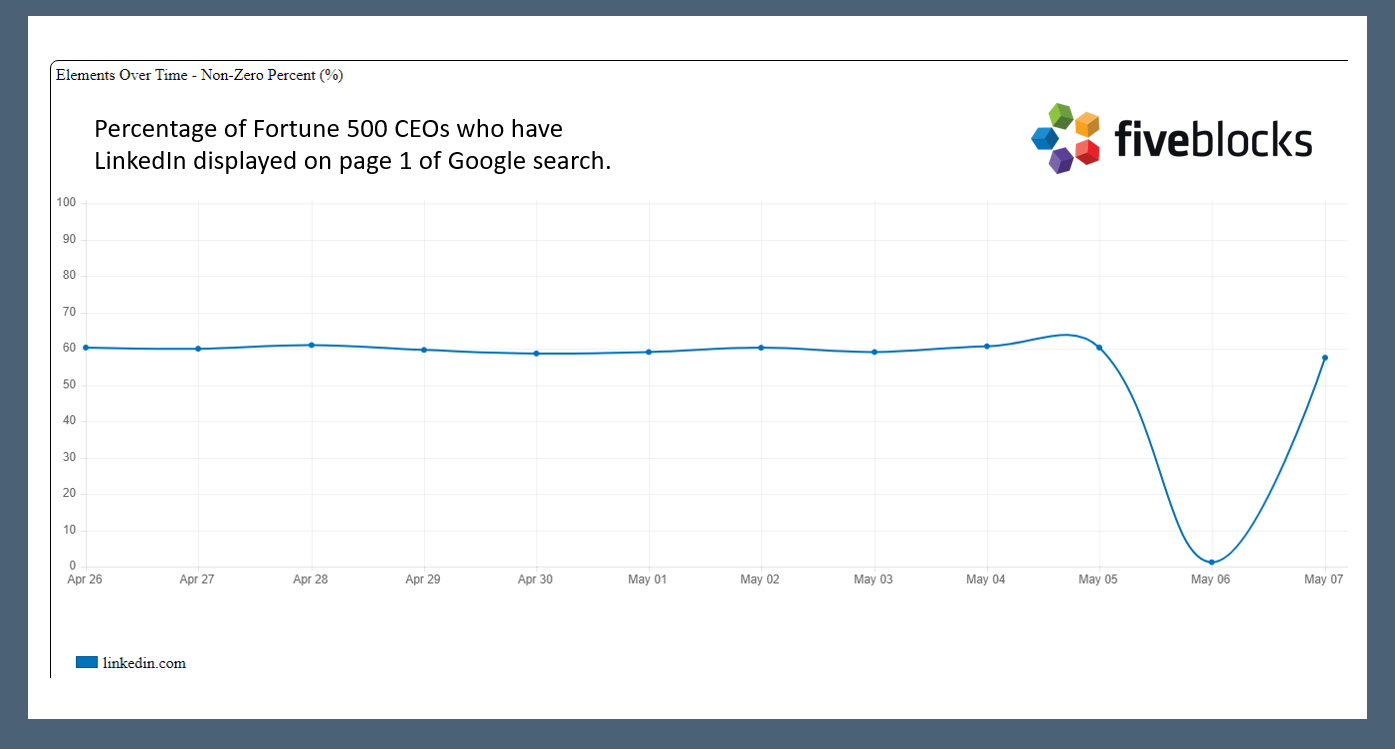

For example, we track the percentage of Fortune 500 CEOs who have LinkedIn displayed on page 1 of their search results.

Usually it is about 55%. On May 6th, none of the CEOs had LinkedIn displayed.

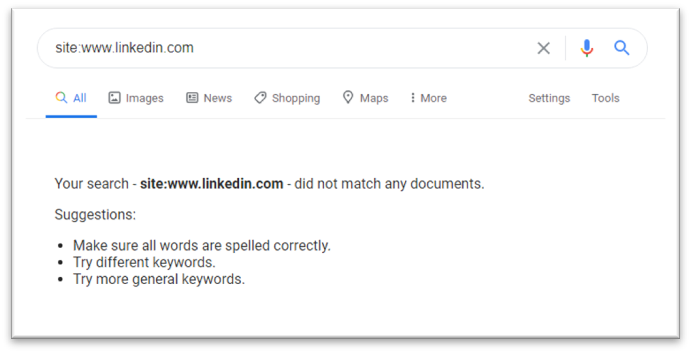

We did not know what caused LinkedIn to disappear, but we did know that the main site was not being included in Google’s search index.

In other words, LinkedIn had been de-indexed by Google.

A search preceded by “site:” shows all the pages within a domain that are in Google’s index. This search showed that no pages from www.linkedin.com were included in search.

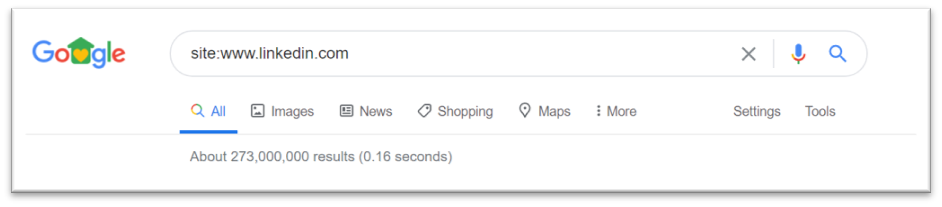

Here is what that search had previously looked like:

The pages still existed, and the site was still live. Someone who went directly to www.linkedin.com would never have noticed this search engine issue.

LinkedIn has country specific domains, which continued to rank in Google. For example, the French site still had all 23 million results appearing in search.

We also noticed that it was an issue specifically with Google.

On Bing, for example, LinkedIn continued to appear in search results.

Initially, we were unsure of the reason for LinkedIn to be dropped from results. It seemed unlikely that Google would choose to entirely remove such a major site. According to Similarweb, LinkedIn is the 26th most visited site in the USA, and over 23% of visitors to the site come via a search engine.

In the past, we have seen the Google algorithm demote sites for various reasons. However, we have never seen Google completely remove a major domain from search before.

It also seemed unlikely that LinkedIn would choose to remove itself from Google search.

Unless it was a mistake.

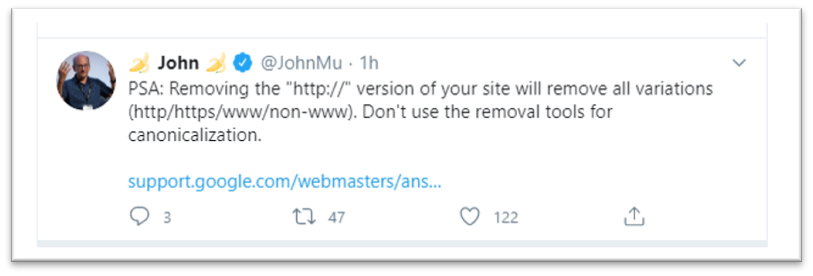

So as one does, we turned to Twitter.

First to notice this massive shift in search results, Five Blocks tweeted about it, looking for answers. SEO leader Barry Schwartz wrote about it on Search Engine Roundtable, and tagged two of Google’s spokespeople in a tweet.

A short while later, John Muller of Google tweeted a PSA which didn’t mention LinkedIn directly, but seems to have provided the clue to what had happened.

We understood this to be a cryptic message to LinkedIn, telling them that someone accidentally clicked a button in Search Console which removed the site from Google search.

Less than 24 hours after LinkedIn fell out of Google, it returned.

The graph below shows that very quickly, the percentage of Fortune 500 CEOs who had LinkedIn displayed on page 1 returned to about the same point it had been previous to May 6th.

IBM‘s and Mary Barra‘s results both returned to their normal state.

All’s well that ends well.

Key Takeaways

The LinkedIn disappearance was a perfect opportunity for Five Blocks and our clients to be reminded of some fundamentals of online reputation management.

Here are some of our takeaways:

- It is essential to continue to monitor results every day. Someone, somewhere, accidentally clicking the wrong button can have an enormous, unexpected impact on search results.

- When LinkedIn does not appear in search it can potentially make results noticeably worse. Conversely, having LinkedIn in search can make results much better. That’s why we encourage clients to create and optimize LinkedIn and ensure that their profiles are indexed.

- We cannot rely too heavily on any one domain when working to improve search results. Even prominent and well-established domains can sometimes let us down. The more we use a variety of tactics and tools to enhance reputation the more secure the results will be.

- The Google Knowledge Panel is totally dynamic. Each time a search is made, Google checks the index to know what to display in the Knowledge Panel. As soon as LinkedIn was de-indexed, it disappeared from the Knowledge Panel. And as soon as the site was re-indexed, the icon reappeared. So, just because the Knowledge Panel looks the way it does now, does not mean it will stay that way tomorrow.

Presidents’ Day: Google’s Complicated Relationship with Alexander Hamilton

We think you will agree that the best US president to focus on this Presidents’ Day 2020 is Alexander Hamilton. You know who we mean: “The ten-dollar founding father without a father,” as he is called in Lin Manuel Miranda’s musical, Hamilton.

Except for one small detail. Hamilton was never president. Nope, not even a little bit. And yet a lot of people, and at least one extremely important non-person, think he was.

Can You Answer This Question?

We conducted a (very) informal survey among our friends and asked them to name a few US presidents. Everyone listed Washington and Lincoln. Almost all of those asked also said, incorrectly, Hamilton.

Our small group of ill-informed respondents is not alone. According to a 2016 study, “about 71 percent of Americans are fairly certain that Alexander Hamilton is among our nation’s past presidents.”

In fact, most Americans are more confident that Hamilton was president than they are about half a dozen actual presidents.

But we shouldn’t shame people who either weren’t around when that Got Milk? ad came out, or can’t afford hundreds of dollars for a ticket to a Broadway show, for not knowing American history, can we? Or maybe we can, since there is a great source of information available, entirely for free, at the tips of their fingers.

Or is there?

Go Ahead and Google It.

We are referring to the internet, of course. We have outsourced the data part of our brain to the all-knowing Google.

So, who (is Google a “who”?) better to correct our error about Hamilton? Let’s have a look at what Google has to say about our beloved President Hamilton.

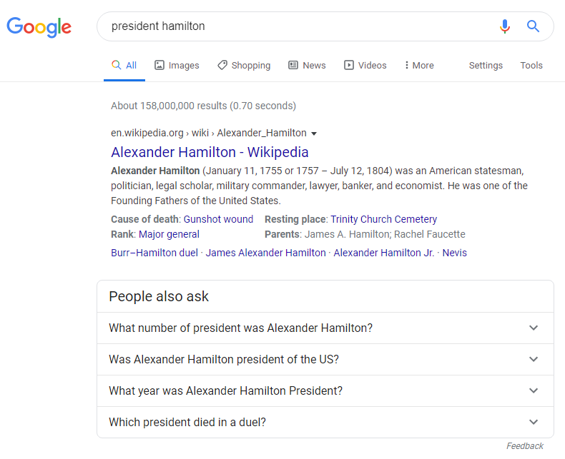

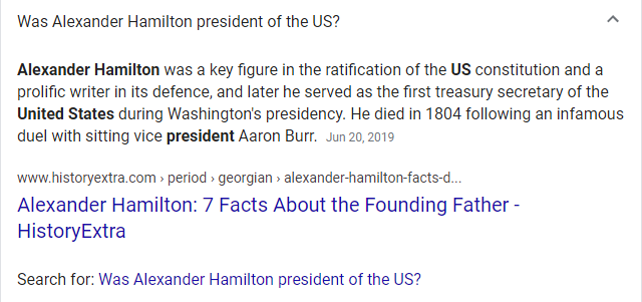

If you search for “President Hamilton,” Google does not display a screen saying, “No, you are mistaken.” Rather, it disappointingly encourages the error in its “People also ask” section, with the following four questions (sic):

What number of president was Alexander Hamilton?

Was Alexander Hamilton president of the US?

What year was Alexander Hamilton President?”

Which president died in a duel?

Even when you look at the answer to “Was Alexander Hamilton president of the US?” Google seems confused and doesn’t give you a straight yes/no answer.

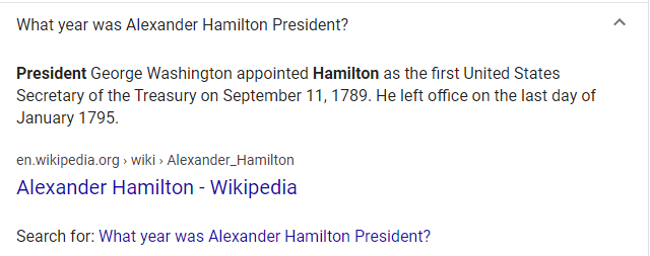

Similarly, the answer to “What year was Alexander Hamilton President?” is not the correct answer of “never,” but rather somewhat avoidant:

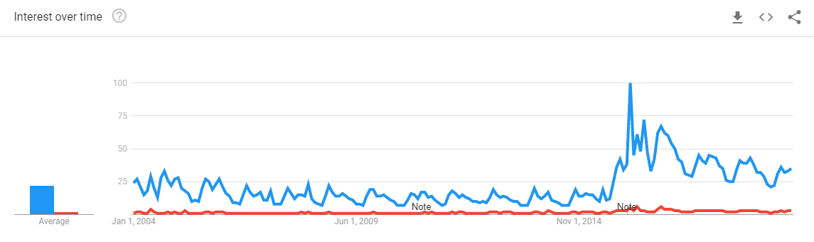

Fewer people search for “President Hamilton” than for “Alexander Hamilton.” There was a huge spike in the number of searches for “Alexander Hamilton” around the time the musical came out. More and more people wanted to know who he was.

Indeed, things are marginally better if you search simply for “Alexander Hamilton.”

The second and third questions still imply that he was president, whereas question four actually confirms that he was never president.

At least two of the questions imply that Hamilton did serve as president.

As the lyric from the musical goes: “You have no control who lives, who dies, who tells your story.”

Enter “President” Franklin

Google is definitely telling its own story when it comes to Alexander Hamilton. But it’s not just about Hamilton.

If you would be so foolish as to search for “President Benjamin Franklin” (as we were) you would find that Google also fails to set you straight.

We are so used to Google supplying us with information, that we often trust it unquestioningly. Often, that works out fine.

If you ask Google “what is the capital of bolivia”

Or, “who was the actress in casablanca?”

You get a clear answer.

But don’t ask Google, for example, “does Australia exist” since only one result on the page gives the correct answer; Australia does, in fact, exist.

In short, it is up to users to carefully examine each search result, taking responsibility not to outsource the thinking parts of their brains in addition to the data parts.

And just for clarity’s sake, Alexander Hamilton, although a really interesting guy with a talent for rap, was never the President of the United States.

Searching for Boris

If someone has negative results appearing in search, does it make sense for them to try to “deceive” Google by using terms associated with the negative result in positive ways? A meditation on models and buses.

Amid the political drama of Brexit, a hung parliament, and upcoming elections, the virtual Boris Johnson also caused a stir, especially among digital media professionals.

A recent Wired article discussed the fascinating, odd phenomenon of Boris Johnson’s “off script” ramblings, rumored to be an attempt to “game Google.”

It began on June 20, 2019, when Johnson gave a most peculiar interview on Britain’s TalkRadio. He was not yet prime minister of the UK but was already the most likely candidate to replace Theresa May. He was asked what he does to relax. His reply, many will remember, was perplexing: “I make things. I make models of buses.” He went into detail about this unexpected hobby.

Almost immediately, pundits began to suspect there was something more cunning behind Johnson’s answer than the average politician’s disconnect from real people. Maybe, they surmised, it was a calculated move to improve his search results.

You see, Boris Johnson was already famous for another bus – one in which he rode around the country before the Brexit vote, encouraging people to vote to leave the European Union. On the side of that bus, in big letters, it said, “We send £350 million to Europe, let’s fund our NHS instead,” which was a contentious statement, and perhaps an outright lie.

First the social media opinion makers, and then everyone from Gizmodo to John Oliver, suggested that perhaps Johnson specifically spoke about model buses, so that anyone searching for “Boris Johnson bus” would read about the models, not the Brexit campaign.

This seemed unlikely at first. But then, in early September, shortly after media reports that the police had been called to a flat Johnson shared with his girlfriend Carrie Symonds, Boris gave a rambling speech while standing in front of a group of police cadets. Was that another attempt to manipulate Google?

And then on September 29, in an interview with the BBC’s Andrew Marr, Johnson insisted he was “a model of restraint.” The phrase was picked up in headlines across the country and internationally. Coincidentally (or not), he said this a day after police opened an investigation into potential criminal misconduct for awarding state money to model Jennifer Arcuri, an alleged mistress.

Oscar Wilde wrote, “To lose one parent may be regarded as a misfortune; to lose both looks like carelessness.” In the case of Johnson, repeating the supposed “trick” three times makes it seem like an attempt to massage his search results and media.

The question is – assuming it is a trick – does it even work? If someone has negative results appearing in search, does it make sense for him or her to try to “deceive” Google by using terms associated with the negative result in positive ways?

If you looked at the search results immediately after Johnson spoke about his model buses, most of the results were about the models, rather than the Brexit bus. So, it was a clear short-term win. But the Brexit bus was already old news, and Boris mumbling about his hobbies was probably just about as exciting for readers.

Furthermore, a couple of months later, the hobby buses have largely disappeared from search results (though “luckily” for Boris, the company that made the buses went bankrupt, so that has dominated the results.)

With the police and the model diversions, Johnson was less successful. Of the average 10 results on page 1 of Google search, one or two were about the positive spin, most were negative, and a couple were articles like this one, discussing whether or not Boris was intentionally trying to manipulate the results (it’s unclear whether these discussions please Johnson.)

But fundamentally, even if the theory is true and he really was using these tactics to manipulate search, it would be the wrong approach to take for a very simple reason: User behavior.

Someone who searches for “Boris Johnson bus” or “Boris Johnson model” is looking specifically for the “dirt.” Even if, hypothetically, there are no negative results on page 1, someone looking for information on Johnson and Jennifer Arcuri will simply click to page 2 or use more focused search key words until they find what they are looking for. With a specific search like that, there is no point trying to manipulate the results (even if such a thing were possible): you cannot fool the searchers themselves.

Perhaps the PR team behind this initiative got a pat on the back from Johnson – at least they managed to remove some of the negatives for a few days. But in fact, they didn’t really make any difference at all to Johnson’s online reputation.

We spend all day thinking about and working on client’s online reputation, and we know that cheap tricks and short-term fixes are not the way to go. Nor does it make sense to focus specifically on the negative terms, because someone who is looking for the negatives will find them.

Rather, we would be more interested in what search results look like for “Boris Johnson” or “UK Prime Minister.” If someone searches with no preconceived ideas, what do they find?

There is such a constant torrent of news about Johnson and Brexit, that it would be impossible to take complete control of his search results right now. Nonetheless, a search for “Boris Johnson” includes his Wikipedia article (which almost always ranks near the top of page 1 for the subject, and which is supposed to be unbiased and fairly written.) His Twitter account and his Facebook profile both rank on page 1. So, he “owns” two of the results on page 1 (and has a Twitter box, which occupies more space that he controls.)

Let’s look at a couple of senior members of Johnson’s cabinet. Jacob Rees-Mogg is Leader of the House of Commons. Page 1 of his Google results include his Twitter and Facebook profiles, his Wikipedia entry, and his profile on www.parliament.uk.

Chancellor of the Exchequer, Sajid Javid, has results from Wikipedia, Twitter, www.parliament.uk, www.gov.uk, and his own website, https://www.sajidjavid.com. These types of “owned” results occupy the top half of the first page of Google, knocking out negative results and allowing those MPs to more closely control their online reputations.

We don’t know for certain whether Johnson was trying to use tricks to manipulate his search results, but we do know that if he were to ask us, we’d tell him this: Sir, you’d be better off focusing your energy on optimizing www.boris-johnson.com (a site not updated since 2016) and/or populating borisjohnson.com, which is not even live. You could also strengthen your owned results for the search term “Boris Johnson,” rather than speaking about model buses or posing with policemen. Your PR team is welcome to contact us. You can go back to the models.