Unlocking Stakeholder Perception of your Brand Using Google Search Data and AI

Communications and PR professionals often rely on social media and earned media to gauge public perception of their brands or those of their clients. However, there’s a wealth of information hiding in plain sight that can provide even deeper insights into what people really think about your brand and your competitors: Google search results data.

By analyzing the search results for your brand and your competitors, you can uncover patterns of thought, and identify the questions and concerns that your stakeholders have. This is because Google’s algorithm depends on satisfying as many of the searchers as possible. This means that Google is already working to understand what people think and what they want to know. Tapping into this information can be invaluable in making decisions that shape your online presence and addressing potential challenges head-on.

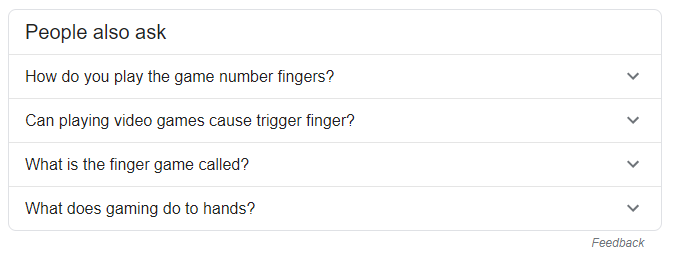

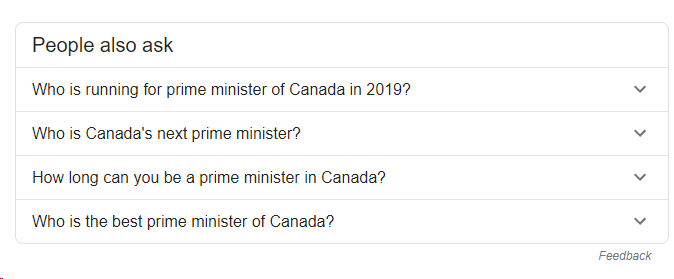

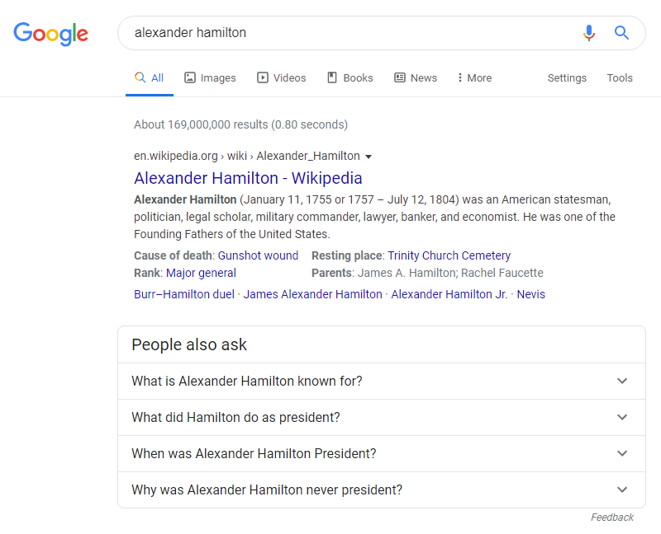

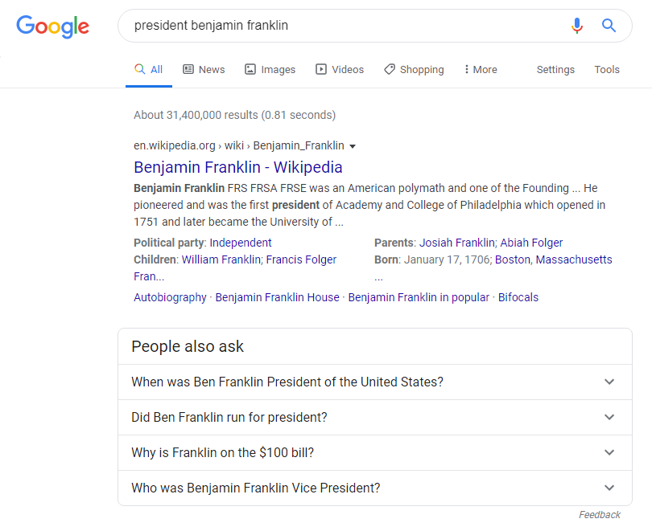

One of the most prominent examples of AI in action on Google’s search results page is the People Also Ask feature. This section typically includes four questions and answers that Google deems most relevant to the search query. By examining these questions across multiple brands in your industry, you can gain a general understanding of what people are thinking and what they want to know about your brand and your competitors.

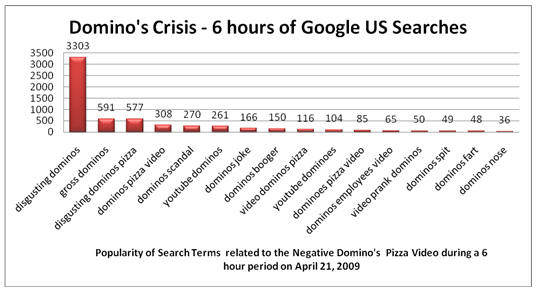

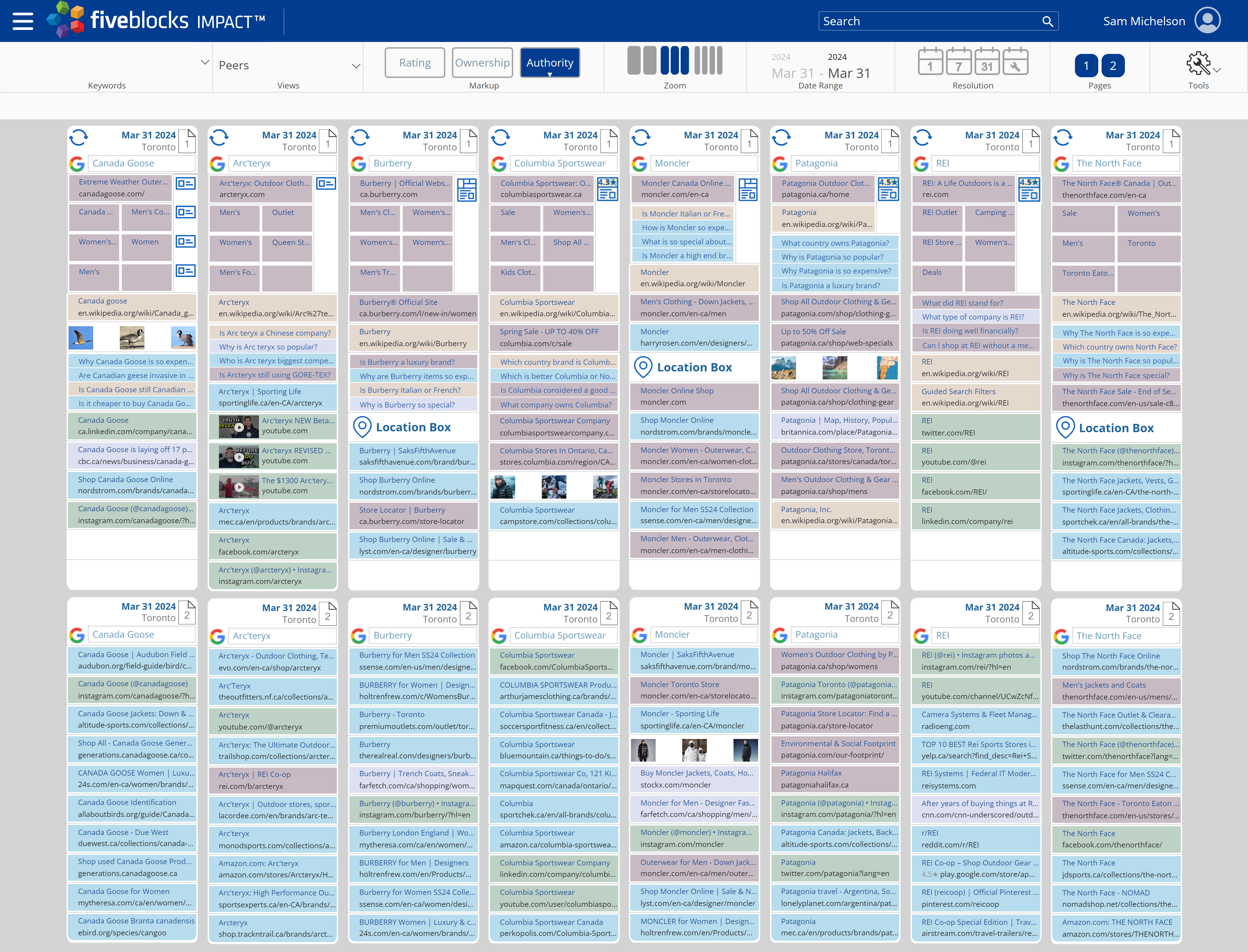

To demonstrate the power of this approach, we used Five Blocks IMPACT™, our tracking and analytics platform, to analyze the search results for several outdoor sportswear brands like North Face, Columbia, and Patagonia on March 31st in North America. We then used an AI to identify patterns in the People Also Ask sections and summarize how each brand is perceived, as well as any obvious challenges and potential lessons from their peers.

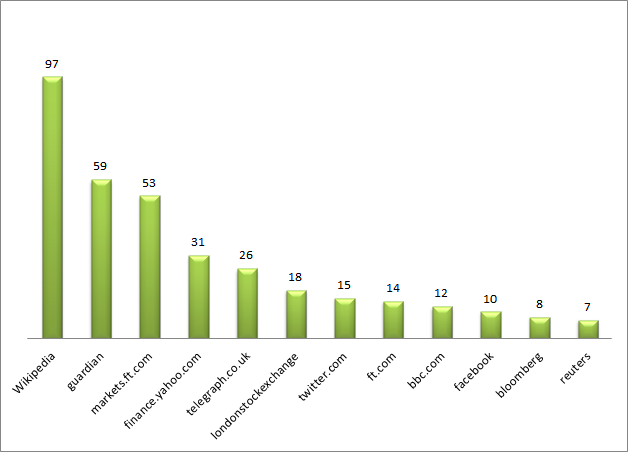

The People Also Ask Questions and Answers collected automatically by Five Blocks IMPACT and then used for this analysis.

The People Also Ask Questions and Answers collected automatically by Five Blocks IMPACT and then used for this analysis.

The analysis revealed some surprising insights. For example, searchers seemed particularly concerned with where each company is based. But the AI went much further, characterizing how each brand is seen by stakeholders, based on the questions asked and providing recommendations for what they could learn from their competitors. While AI models can make mistakes, we found this to be a fascinating instantaneous analysis.

A visualization of search results for various sportswear brands as seen in Five Blocks IMPACT and used for this analysis.

A visualization of search results for various sportswear brands as seen in Five Blocks IMPACT and used for this analysis.

Here are the conclusions that the AI model provided:

Canada Goose

- Seen as an expensive but high-quality and durable brand, known for its premium materials.

- Can learn from Patagonia’s focus on sustainability and ethical sourcing.

Arc’teryx

- Perceived as a popular and functional outdoor brand, with some questions around its Chinese ownership.

- Can learn from Canada Goose’s reputation for premium materials and durability, and from Patagonia’s environmental initiatives.

Burberry

- Firmly established as a luxury fashion brand, with questions about its history and store locations.

- Can learn from Arc’teryx’s technical expertise in outdoor apparel and from Patagonia’s commitment to sustainability.

Columbia Sportswear

- Seen as a good mid-range outdoor brand, often compared to The North Face.

- Can learn from Arc’teryx’s focus on technical performance and innovation, and from Patagonia’s sustainability efforts and brand purpose.

Moncler

- Perceived as a high-end luxury brand, known for its expensive but high-quality winter wear.

- Can learn from Patagonia’s transparency and ethical practices, and from Arc’teryx’s technical expertise in outdoor gear.

Patagonia

- Widely recognized for its sustainability efforts and commitment to environmental causes.

- Can learn from Canada Goose’s reputation for premium materials and durability, and from Arc’teryx’s technical innovation in outdoor apparel.

REI

- Seen as a reputable outdoor co-op.

- Can learn from Patagonia’s strong brand purpose and environmental initiatives, and from Arc’teryx’s technical expertise in outdoor gear.

The North Face

- Perceived as an expensive but high-quality outdoor brand, with some questions about its popularity and branding.

- Can learn from Patagonia’s sustainability efforts and brand purpose, and from Arc’teryx’s technical innovation in outdoor apparel.

Using only Google Results of peers, we can then paint a picture of how Google, and perhaps their searchers, see each brand.

A visualization of what we learned using this Data and AI analysis of the Google Results.

Using AI-powered search data analysis, brand and communications directors can identify areas where their brand’s image might not align with their goals and adjust their digital reputation management strategy accordingly. This data serves as a kind of insightful preliminary focus group, providing valuable insights that can be tracked over time.

In today’s fast-paced digital landscape, staying on top of how your brand is perceived is more important than ever. Leveraging the power of AI and search data analysis, you can uncover hidden insights, address potential challenges, and ensure that your brand is resonating with your target audiences.

Five Blocks specializes in digital reputation management, combining cutting-edge technology and personalized service to help our clients overcome digital reputation challenges. Our advanced data analysis and AI-powered insights allow us to identify the root causes of various issues and uncover overlooked opportunities for improvement. We work closely with your communications team to develop and implement sustainable solutions that deliver long-lasting results. For more information or to see what we can do with your brand’s data, contact us.

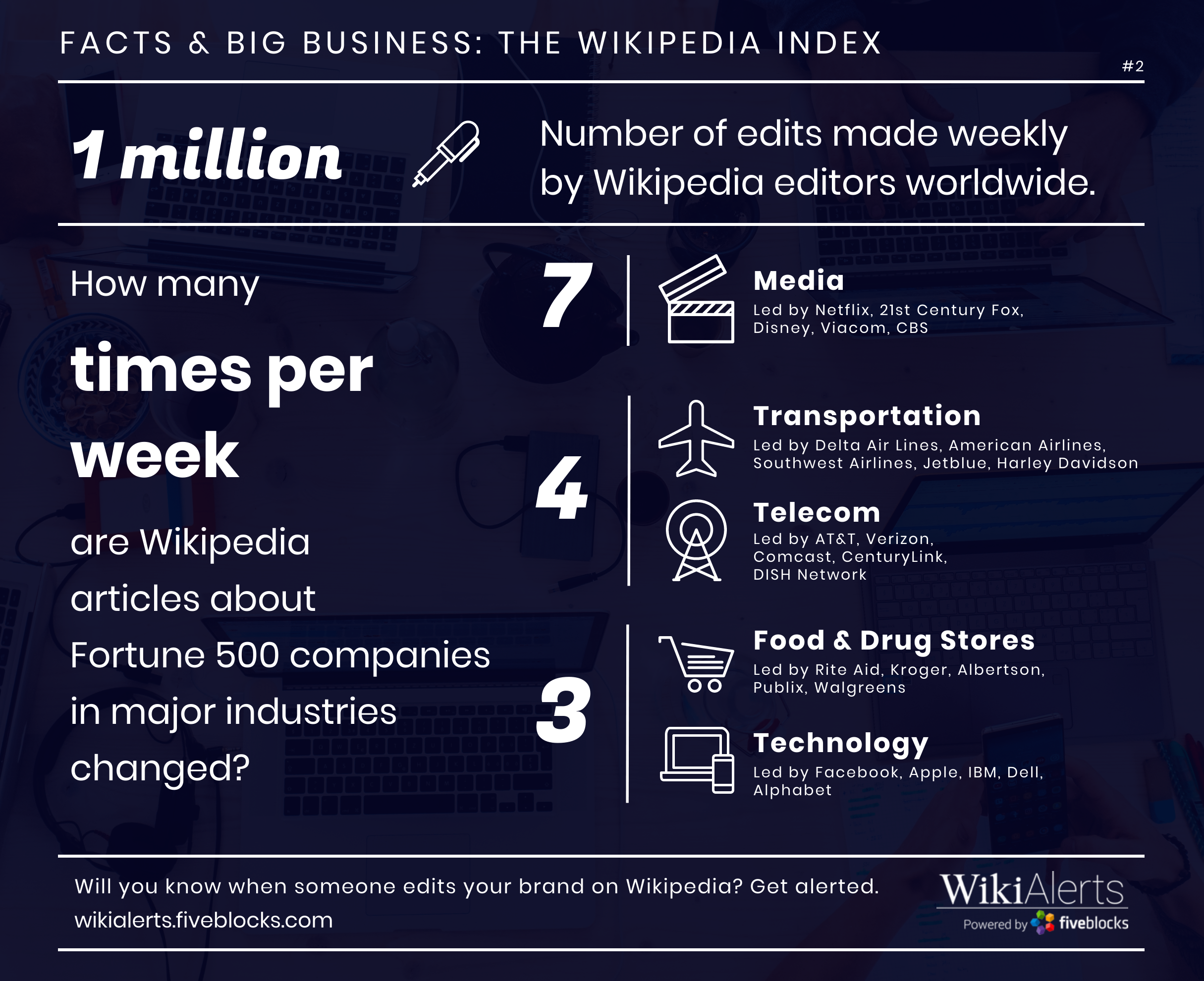

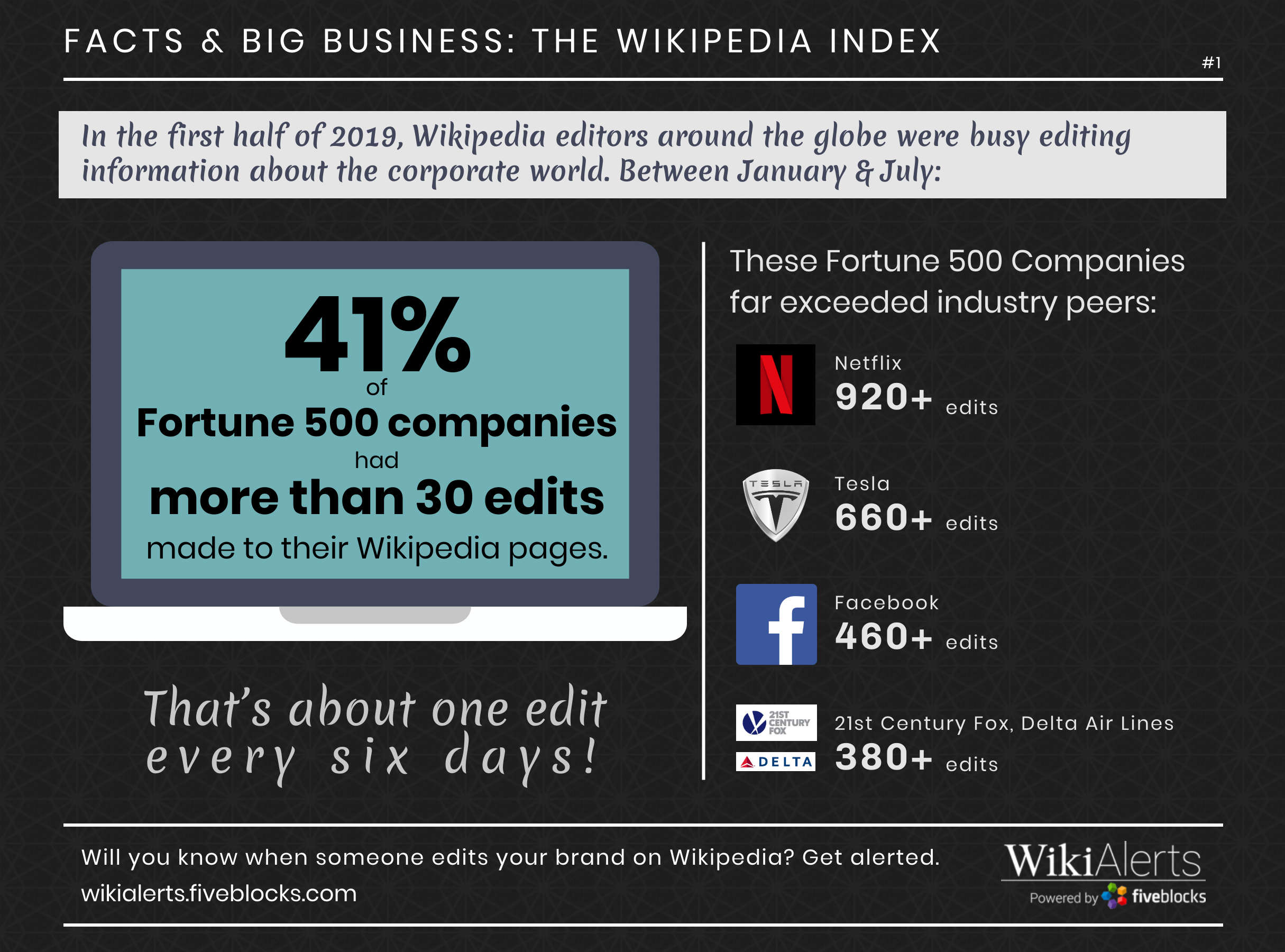

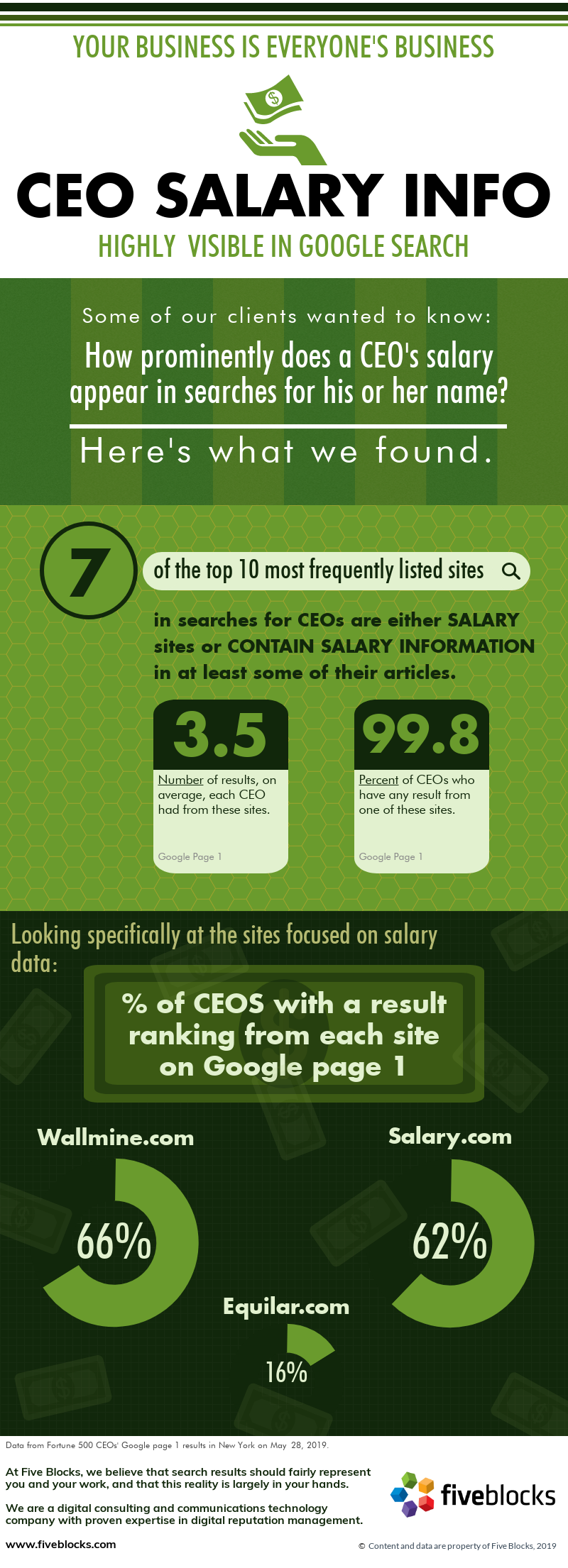

The Future of Wikipedia in the Age of AI

As the use of AI models increases, the way users seek information is evolving. Queries are becoming more complex and conversational, and results are typically based on a much larger body of data, rather than a specific source or page.

As these models become increasingly integrated into our daily lives, the importance of Wikipedia in shaping brand reputation cannot be overstated, since it is a major source for training AIs.

Importance of Wikipedia in AI Training

According to The New York Times, “Wikipedia is probably the most important single source in the training of AI models.” The platform’s vast trove of crowdsourced knowledge, covering a wide range of topics, provides invaluable data for AI models to learn from. Without access to this information, the development of current generative AI capabilities might not have even been possible. (Here’s some additional information on how AIs/LLMs/Chatbots are trained.)

Impact on Brand Reputation

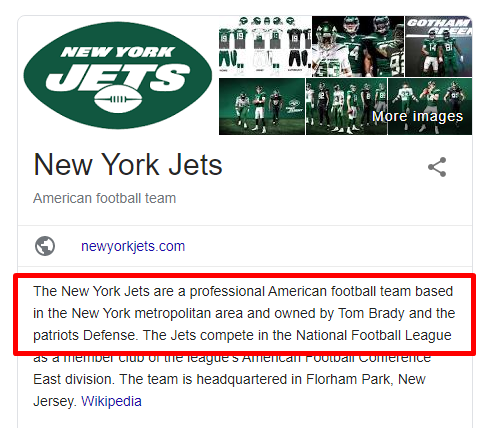

With AI models like ChatGPT, Claude AI, and Gemini having been trained on Wikipedia, inaccurate or biased information on the site can lead to negative or incorrect information about a brand, potentially harming its reputation. With so much riding on the underlying information in Wikipedia, ensuring the positivity and accuracy of a brand’s Wikipedia presence has become more important than ever.

Recommendations

Given Wikipedia’s elevated status, our recommendations for companies, brands, and individuals are to work within the Wikipedia guidelines to do the following:

- Maintain: Create and/or maintain a well-structured, robust Wikipedia page for your brand or personal profile.

- Update Accurately: Make sure the page remains updated and accurate with current facts, figures, and noteworthy achievements.

- Include more sources: Since LLMs utilize all of the content, include as many relevant, verifiable sources, as appropriate – these should only help the AI training.

- Go Multilingual: Consider developing a presence across multiple language editions of Wikipedia. LLMs often learn from content in various languages, and the more you play an active role, the better. Also, consider that English is often the hardest language version of Wikipedia to impact, and other language versions can be very easy to edit.

- Other Wiki pages: LLMs can learn about your brand and industry from any Wikipedia article, so consider getting relevant information added to relevant industry articles, not just the ones about your brand.

- Talk Pages: Leverage Wikipedia’s “Talk” pages to include additional relevant information, as LLMs may also use these for training.

- Images: Consider submitting relevant images via Wikimedia Commons to enhance your Wikipedia page and improve AI model understanding.

- Categorize: Utilize Wikipedia’s category system to ensure your page is properly categorized and connected to the ideal topics.

- Monitor: Monitor your Wikipedia presence for edits that may introduce inaccuracies, outdated information, or bias; address issues appropriately and promptly. Do the same for other relevant pages related to your company or brand. Our free WikiAlerts service provides tracking of Wikipedia and Talk pages.

- Wikidata: Beyond Wikipedia, leverage Wikidata, Wikipedia’s sister project, a powerful database of community-contributed structured data that LLMs will increasingly use to verify facts.

Do We Even Need Wikipedia in a World of AI?

An interesting question that has been raised recently is whether there is even a need for Wikipedia. Since the content is taken from various third-party sources, and the LLMs presumably have access to the sources and probably many more, why can’t an AI produce Wikipedia content that would be as good or better than content created by Wikipedia editors?

To answer this question there have been various attempts to utilize AI to write sections of Wikipedia pages, but so far, despite the great capabilities of AI, they have not been proven to produce content that is up to par. It is possible that this will change at some time in the future, but for now there still seems to be tremendous benefit derived from the human (crowdsourced) process that helps create a Wikipedia page. Perhaps AIs that are trained on this process will eventually produce content that is recognized to be of high enough quality.

Conclusion

Ongoing tracking of how AI models represent your brand, and what role Wikipedia may be playing, can help you identify areas for improvement within Wikipedia and beyond.

As the use of Wikipedia in AI training continues to grow, we believe that the future of brand reputation management will be even more closely tied to Wikipedia. By actively managing their Wikipedia presence, companies can ensure that AI models have access to an important trusted source of accurate and up-to-date information, ultimately leading to a more positive online reputation.

Five Blocks specializes in digital reputation management for platforms including Google and Wikipedia, combining cutting-edge technology and personalized service to help our clients overcome digital reputation challenges. Our advanced data analysis and AI-powered insights allow us to identify the root causes of digital reputation issues and uncover overlooked opportunities for improvement. We work closely with your communications team to develop and implement sustainable solutions that deliver long-lasting results.

For more information or to see what we can do with your brand’s data contact us.

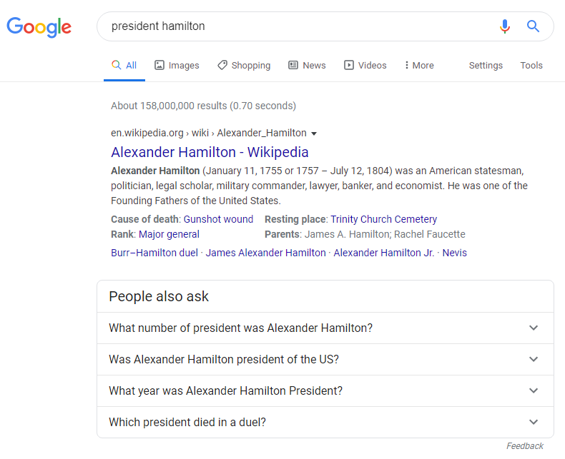

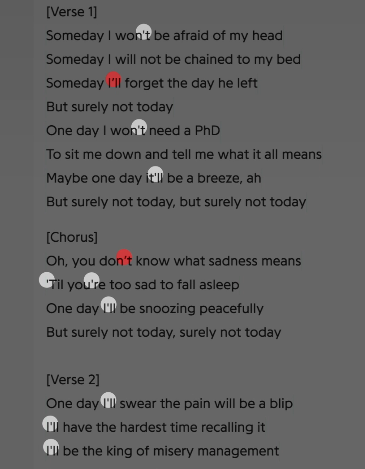

People Also Ask: Your Answer May Be a Question!

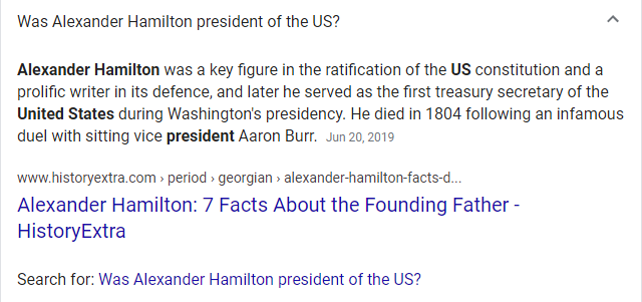

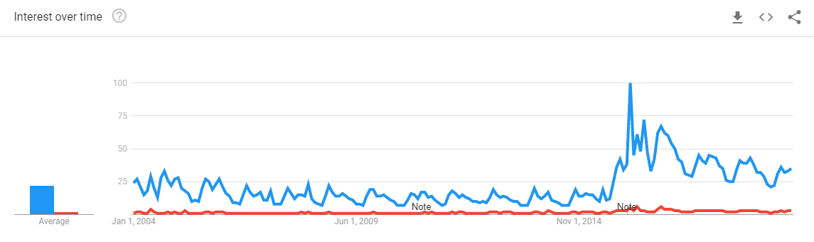

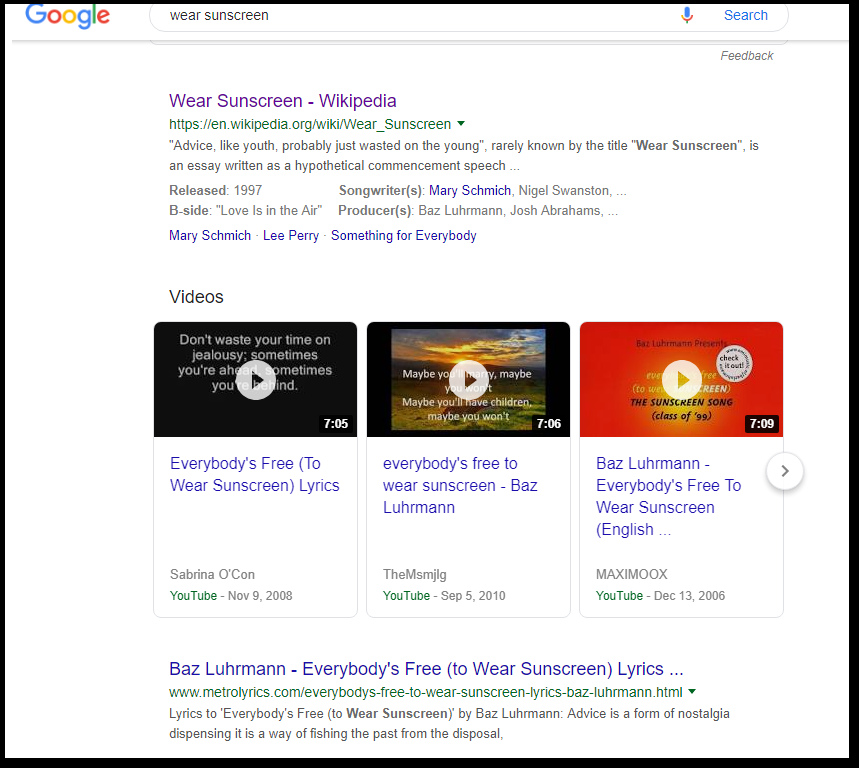

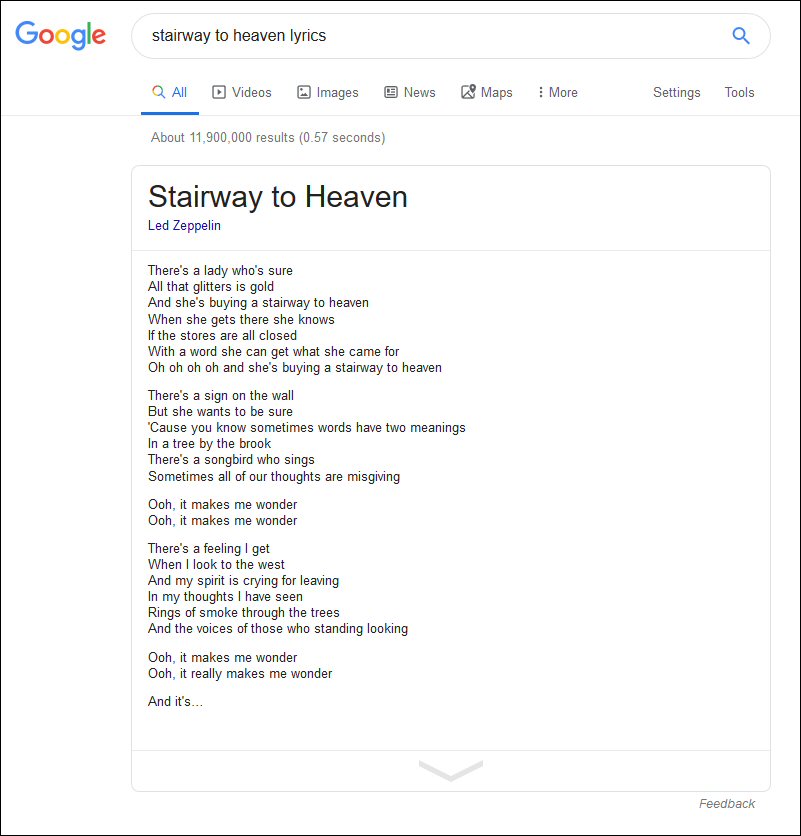

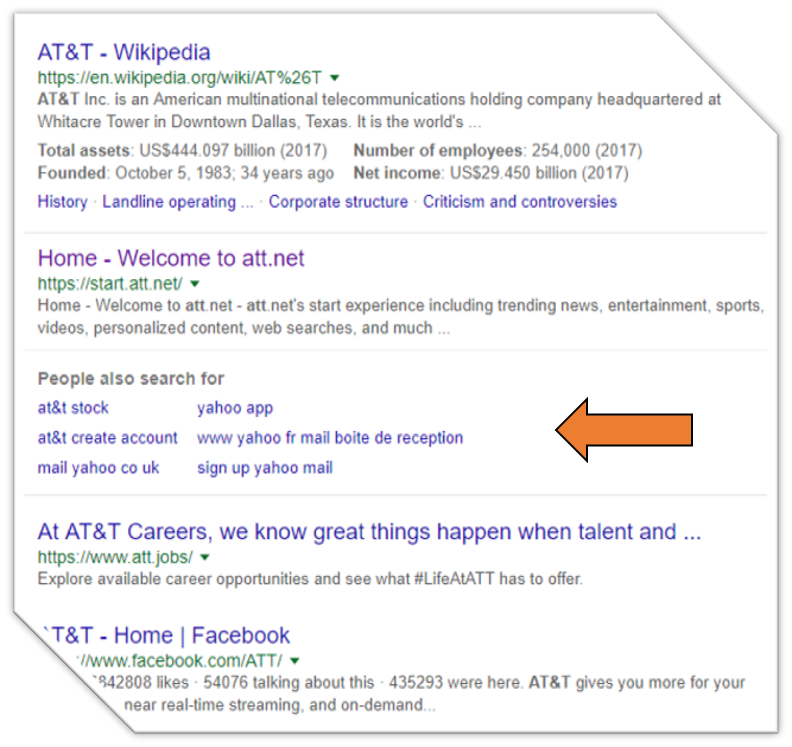

Google’s People Also Ask Box has become an increasingly prominent feature on page one of search. Usually you will see it as a section in the middle of the Google search results page, featuring 3 or 4 questions.

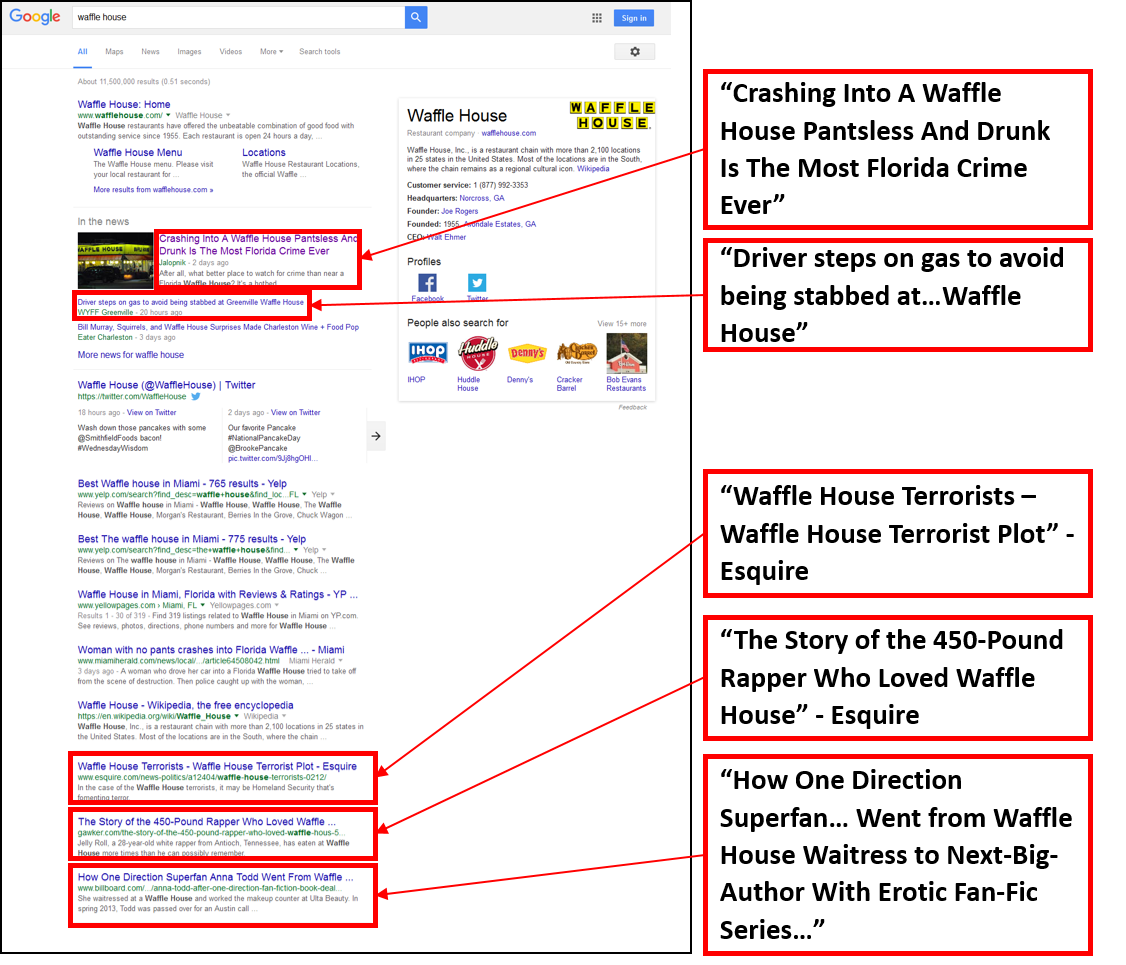

Many companies have noticed that searches about them bring up some bizarre and seemingly contrived questions (“Why is X so bad?”). They wonder if there’s anything that they can do about not only the answers, but the appearance of these types of questions themselves.

The short answer is yes!

But let’s back up for a moment.

People Also Ask: About the Answers

Given that nearly all major companies and CEOs have this feature appear in searches for their name, we’ve recommended in previous articles that brands should own some answers. This means tailoring content, particularly FAQ sections, around real research into what Google typically shows searchers about the company, individual, or related searches. Providing relevant answers would be a way to capture the sources of the PAA for those questions.

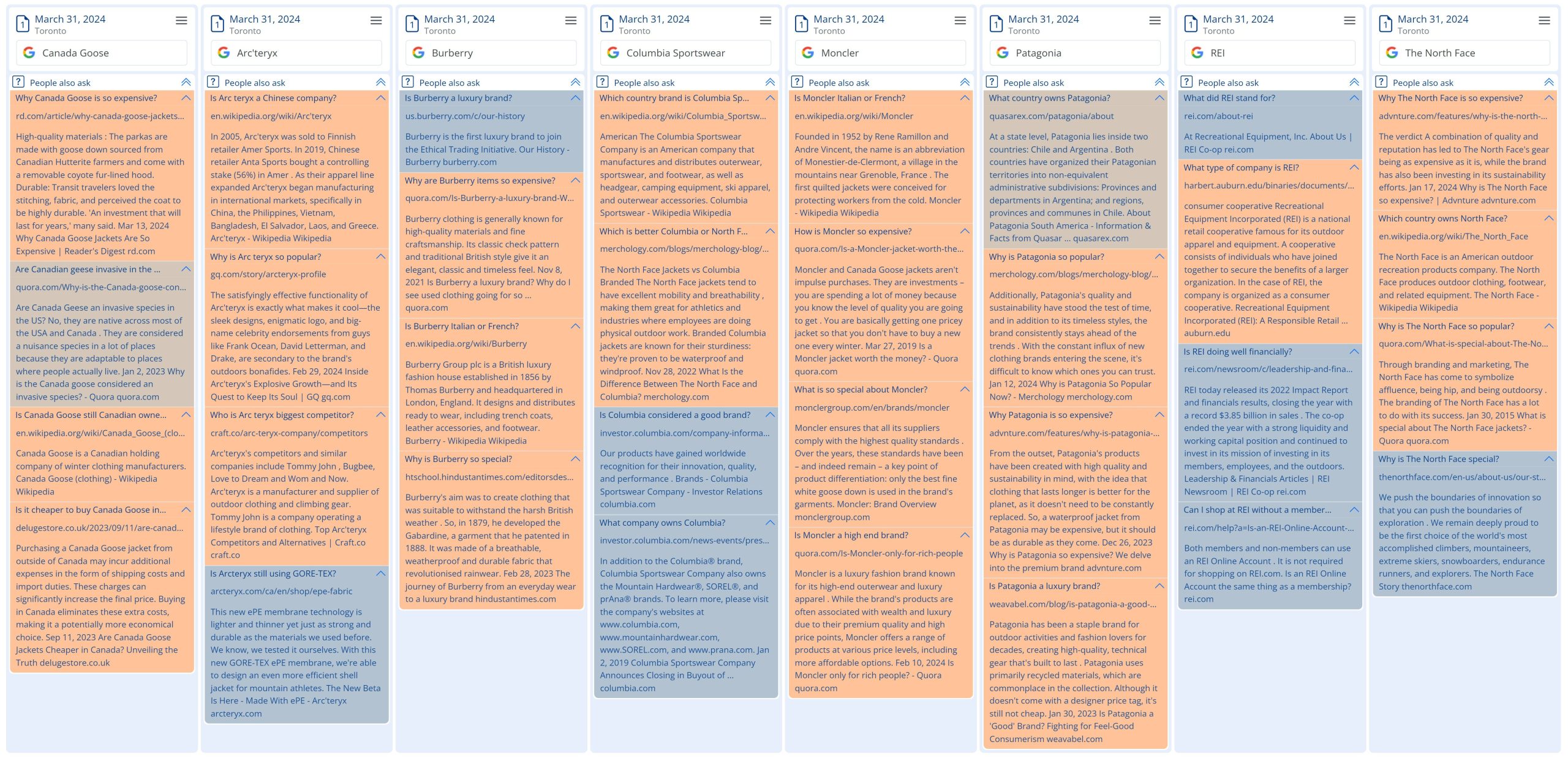

In late December, JR Oakes wrote an extremely insightful article in Search Engine Land, about his research on the PAA feature. His analysis explores themes, sources, and sentiment in questions about companies, and the article concludes, worryingly, with the observation that “the PAA results seem dissociated with actual user search interest and more driven by the content that is available online.”

But perhaps therein – with the content – lies opportunity.

PAA Questions, Sliced by Industry

Five Blocks tracks the search results for tens of thousands of keywords on a daily basis. We wondered whether by analyzing our collected data we might be able to provide additional useful guidance on PAA best practices. Are there specific strategies that brands can use to exert more control over the questions and answers section?

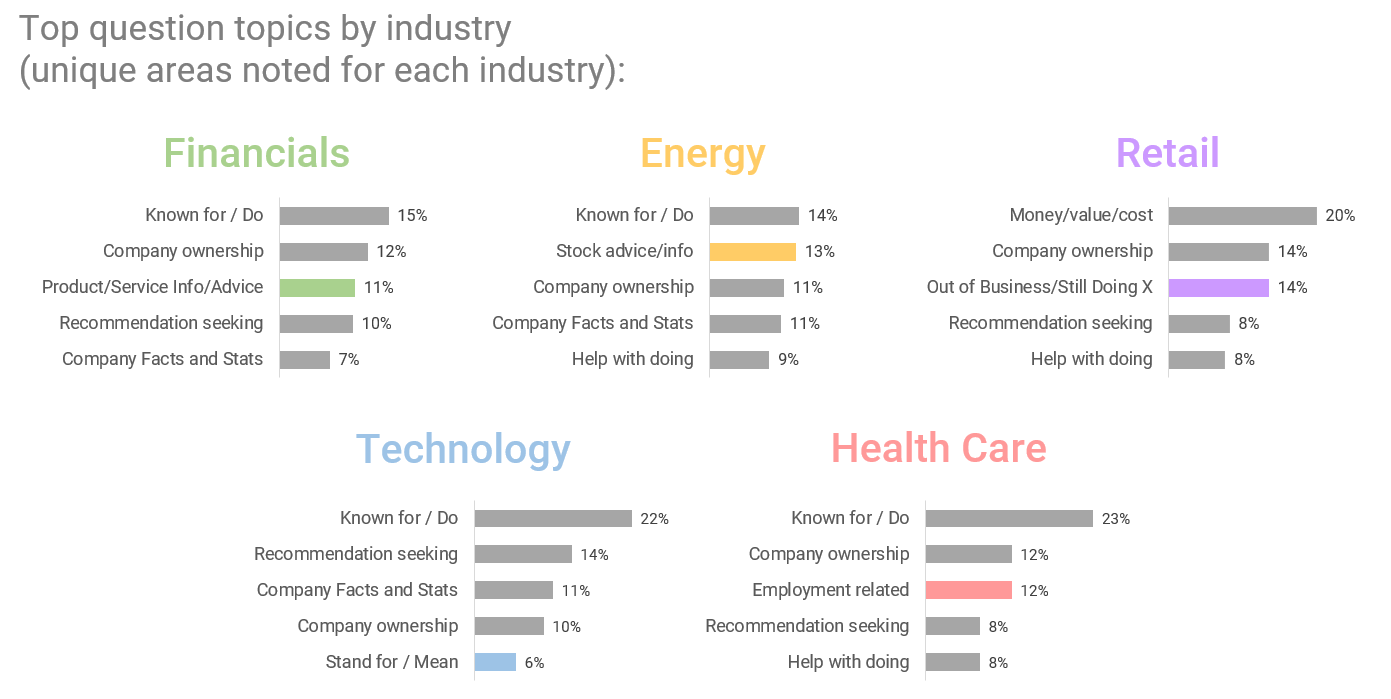

We looked at Fortune 500 companies over the first week in December ’20, as searched in New York.

Over the course of the week, most companies had five to seven different questions showing on the first page of their Google results. The Retail industry had the greatest variety of questions, with 7.5 different questions on average per retail company compared to an average of about 6 for all other industries we studied.

The top five topics included in PAA questions account for about 50% of all questions asked across major industries (Financial, Energy, Retail, Technology, Healthcare.)

These topics are:

- What is the company known for / what does it do?

- Who owns the company?

- Is the company / service recommended / better than competitors?

- Company facts and stats

- Help with doing (eg: How can I access my bank account?)

There are also industry-specific questions that we see among the top five.

The Energy sector, which includes companies like American Electric Power and NextEra, has stock questions appearing prominently.

The Technology sector (CDW and Amphenol, for example) elicits questions about what the company name stands for or means (as these names are often “made up words”).

So…what can companies do if unwanted, irrelevant questions pop into the PAA?

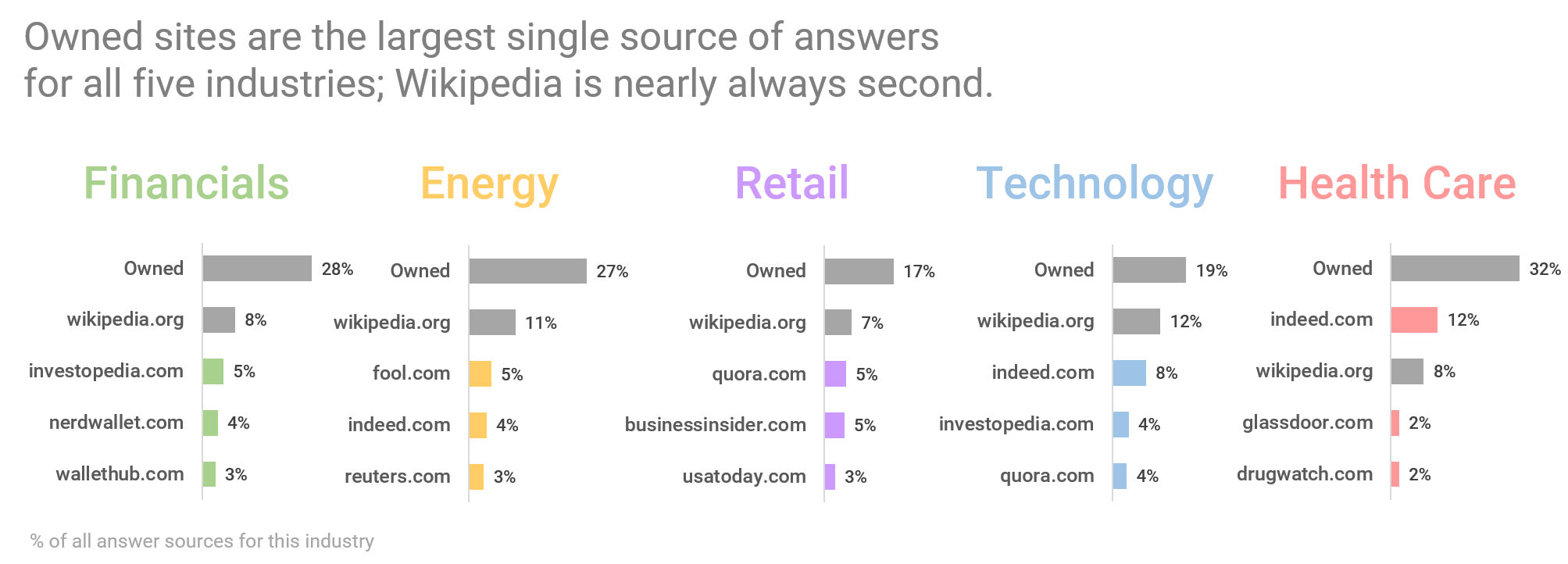

As mentioned at the beginning of this article, owning content related to searcher questions is key – since available content online does seem to drive both the questions Google presents and the answers to those questions.

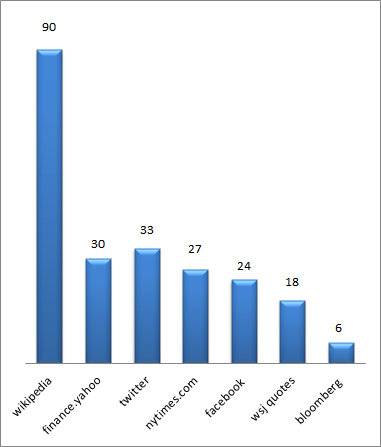

Since owned sites (a company’s corporate website and social media, for example) account for the largest slice of answer sources across industries studied, followed closely by Wikipedia, maximizing the potential of these sources is a good practice for companies.

Also worth noting:

- Owned content sources that end up in the PAA is most prevalent in the Healthcare industry, and least common in Technology and Retail. In these last sectors, Wikipedia is also less popular as an answer source.

- Answers to questions shown for retail companies like Dillard’s come from a larger variety of sites than in other industries. This is likely because there is a larger assortment of questions shown for retailers than for other types of companies.

- Interestingly, Quora is a top answer source for both the Technology and Retail sectors, indicating that Google is willing to trust crowdsourced responses as reliable enough to include as answers to these types of questions.

- Within the Healthcare sector, notable answer sources include both Indeed and Glassdoor, suggesting many of these questions relate to employment.

There are some additional actions that companies can take to “change the conversation”:

- Companies should make a point of knowing what types of questions are asked, not just about them specifically, but about other companies in their industry.

- While the general types of questions by industry are likely to remain stable over time, current and world events can yield opportunities for companies and brands to provide timely answers to relevant new questions as they arise.

- For example, right now we are seeing many questions for retailers asking if they are still around or out of business. This suggests that, during a crisis, retailers may want to remind customers of ways they can do business, even as storefronts are temporarily unavailable. It also means that brands should ask and answer those specific questions explicitly on their website, such as: Yes, we are open 24/7, via our website.

- Although questions related to the legitimacy and trustworthiness of a company are infrequent (we saw these at low levels and only for financial, tech, and retail companies), they can be impactful on a searcher’s perception of a brand. Companies need to regularly monitor the questions Google shows for them and, as mentioned above, leverage content that will negate unfavorable ideas suggested by these questions.

- Note that different searches bring up different questions (“Can I do X” may bring up different questions than “Can you do X”), and that clicking on a question brings up new questions. The best practice is to be aware of the various types of questions and to be sure to have content that asks and answers as many as possible.

Navigating Wikipedia: A Basic Guide for PR Professionals

It happens all the time: We are consulted by PR firms with the question: Why is a certain request for a Wikipedia article consistently rejected by the editor community? One firm told us, in exasperation: “Our client is a noted professional in her field. She has 30,000 followers on social media. She has appeared on television a few times. Her results, for credibility reasons, should surely include Wikipedia. Why is relative fame not enough for Wikipedia? What on earth does it take?”

Great question! Here is our answer.

Wikipedia Land, located at the top of the information stream, is hard to navigate without a map. Many great PR teams get lost there, and could potentially save themselves much time and trouble by better understanding the routes the experts take. (See here for more on editing Wikipedia.)

Here are some notes, compiled from the advice of some of my colleagues, who are experienced trekkers.

- Notability is the gold standard for a page on Wikipedia (see why this is, below.) This is not the same as being well-known. Having a podcast, or appearing as an expert on TV, can sometimes help with Twitter verification; but they are not sufficient for Wikipedia. The theoretical bar for notability in Wikipedia generally amounts to something like: If we were writing a big encyclopedia for a time capsule, this person or entity would need to be included.

- Since this is so hard to prove, the gateway becomes sourcing. Notability on Wikipedia is determined by legitimate sources, as follows:

- Sources need to be independent (i.e.: not the company’s own website, self-published corporate history, or a press release) and from a reputable, non-tabloid-type source (eg: The Wall Street Journal works great, but The Daily Mail won’t fly.) You generally need three or more of these to help you to get over the notability hump – but there is no exact formula here.

- The sources you cite need to be largely ABOUT the individual or company in question. Sources that mention the entity in passing (e.g. your client is mentioned in a list of top twenty women in education) will generally not do the trick.

- Wikipedia doesn’t accept content that is generated or spoken by the subject of the article for most purposes. However – there are exceptions to this rule, namely, uncontroversial, easily provable statements that the subject makes about themselves (e.g. “Born and raised in Topeka, Kansas.”). Interviews are often not regarded as a good source for most claims, unless the journalist makes independent observations that support the assertion made in the Wiki article.

- On a related note, there is a separate issue of verifiability: The sources you use should expressly support the claims you make on the page as everything written on the page needs to be backed up by legitimate sources. For example, if you are a well-known pediatrician, and are extensively quoted in articles about a nutritional health crisis, these sources would still not be useful to support a statement such as “Dr. X is 55 years old and a graduate of Duke Medical School,” unless this is mentioned in the article. In other words, the source must support the information you want to present in a direct way.

PR teams working to secure press for clients obviously have several goals in mind, but if getting clients to the point of Wikipedia notability is one of these goals, aim for multiple, independent sources that are reliable; intellectually independent of each other; independent of the subject; largely about the subject of the article; and which speak to the statement made (or which the client wishes to make) on the Wikipedia page.

So, for an archaeologist, an article in the New York Times about their innovative method of determining the age of artifacts would ideally be complemented by a trade journal article talking about recent discoveries, and a career highlights profile in a local magazine from their proud hometown, which would cover some biographical facts they wish to have on the page.

By the way, we know many people have flouted these rules in the past! But editors will eventually catch up to those old pages that went up in a shoddy way, and they can get flagged and suddenly taken down. Don’t look at Wikipedia articles created a decade ago and ask why that person got away with less; it is a brave new world, and these rules are much more strictly enforced now.

A few more notes:

- Language on Wikipedia can never be promotional or sound like it was written by a marketing team. A company can be an “industry leader” if that is borne out by a source, but “America’s best-loved brand” type-language would not pass muster. A company’s mission statement belongs in a section describing its marketing efforts.

- Images need to be copyright free – since the rules of Wikipedia state that anyone surfing the internet can use the image. It is essential that whoever holds the copyright has released their rights to compensation for re-use on Wikipedia and elsewhere on the internet. (There are different types of licenses with different limitations and requirements, for instance, to mention the photographer’s name, or to not be able to change the photo in some way, but the crux of the matter is giving up the main copyright for compensation in order to reuse.) There are exceptions to this, most importantly regarding logos. A company’s logo can be used in a Wikipedia article without the company relinquishing copyright. This is justified based on a fair use rationale – the company still owns the copyright, but the logo may be used on Wikipedia anyway.

If you find yourself challenged by these rules, you are not alone. Even future Nobel Prize winners are not spared this indignity! We explored the notability guidelines, and their sometimes curious effect of barring truly notable individuals from the door, in this article about the physicist Donna Strickland.

Of course, if you are having trouble traversing this strange landscape, you can always turn to us, your trusty guides, for advice and direction.

Google’s Continuous Scroll: How long is page 1, really?

Google announced in late 2022 that they would be rolling out a “continuous scrolling experience” for English language desktop searches performed in the United States. (Mobile users will note that they have been seeing results like this since late 2021.) This means that when you search on Google and reach the bottom of page 1, instead of clicking to go to page 2 of search, Google automatically adds the next page of results to the bottom of the current page. The new user experience is more like Facebook – as you scroll, you get more choices for engagement.

Obviously, this challenges the old reputation management wisdom that a client’s primary concern should be mostly about page 1, with subsequent pages being less relevant. How should we be defining “page 1” now?

As it turns out, there are several reasons not to worry, and some best practices that emerge from this change.

Firstly, Google’s algorithm and its set of features are constantly changing, and many features like this have been rolled back in the past. Features on Google are somewhat fluid, so watchful / prepared is much better than panicked.

Secondly, the core search algorithm has not changed, and we therefore do not anticipate a sudden drop in page 1 satisfaction and an increase in demand for a second page of results, no matter how the next set of search results is loaded. Unlike social media platforms like Facebook and TikTok which endeavor to keep you engaged with them for longer periods, Google’s stated focus has always been on satisfying user’s communicated search intent quickly – minimizing your time on their site, and guaranteeing you come back habitually. This is part of Google’s DNA and is unlikely to change.

And in fact, industry clicking and eye tracking studies since the mobile roll out have consistently shown that the first 10 or so results still satisfy over 90% of searchers.

Here’s the “But”…

That said, more accessible and efficient transitions typically lead to those transitions being utilized more frequently by users. The larger screens on desktop devices could also increase the number of search results seen when the next page loads. We therefore anticipate a small but noticeable increase in desktop impressions and clicks for page 2 search results.

That means that Page 2 matters a bit more. Field data we saw following the mobile continuous scrolling launch suggested that this change made page 2 results more easily accessible for users, and impressions (eyeballs) on page 2 mobile results increased by around 10%, although the impact on clicks to these results was less noticeable.

Bottom line: brands and individuals should continue to prioritize ownership and control of their online narrative as reflected by the quality of their page 1 Google Search results. Ensuring that this first set of results fully addresses and satisfies searchers’ varied intents is the best way to obviate the need for searchers to continue scrolling past page 1.

For those with prominent unfavorable content in page 2 search results, we recommend dedicating more time and resources into expanding their ownership and control over page 2 moving forward, because these results may now be seen more frequently by searchers.

AI and the Future of Digital Reputation

Over the past month or so, the internet has been buzzing about the new ChatGPT bot by OpenAI. This moment has been coming for a while, in which AI seems almost ready to take a seat at the human table.

And now the humans are excited. I spent way too many hours asking the chatbot to write sonnets for my kids and sitcom scripts (including a scene from The Good Doctor in which he has to treat a marshmallow who has been badly burned in a fire; At one point the marshmallow actually says to Dr. Murphy, “But I’m a marshmallow!”) All this is making many of us a bit nervous. What does this new technology mean for jobs, education, and relationships? What does it mean for human intelligence?

From a business perspective, one of the questions that interests me the most is: How will a new, pervasive reliance on AI potentially impact the digital reputations of brands and individuals?

There have already been numerous articles written on the subject, many of them with doomsday predictions about the coming irrelevance of everything we once knew. In particular, the New York Times raised a series of challenges that this new technology would pose to Google’s revenue and ethics models, as the company evolves its AI strategy.

As usual, I am more optimistic about our capability to incorporate this new technology wisely.

Google vs OpenAI

Right now, when we want to know about a person or a company we Google it, and we see a list of results that the algorithm thinks (based on various factors) will satisfy the searcher. Deciding which of these results to read (or scrolling on) is up to the searcher, as is constructing a conclusion on their basis.

The search page gives us pieces of information to choose from, but we do the work of picking which ones to read, and analyzing what we read. Searching the way we do now gives us an opportunity to consider: Is that what I really wanted to know? Is there important context available that I might be missing? Do those sources look reliable? Is there bias I am missing?

ChatGPT makes the leap from providing information to performing analysis and stating conclusions. Like Google, it makes some algorithmic decisions about which information to use in its analysis (though less transparently, since it does not typically share sources), and then does its own thinking and analysis in order to provide a cogent answer – one that requires very little work from the searcher. And one that may seem satisfying, in easily accessible language.

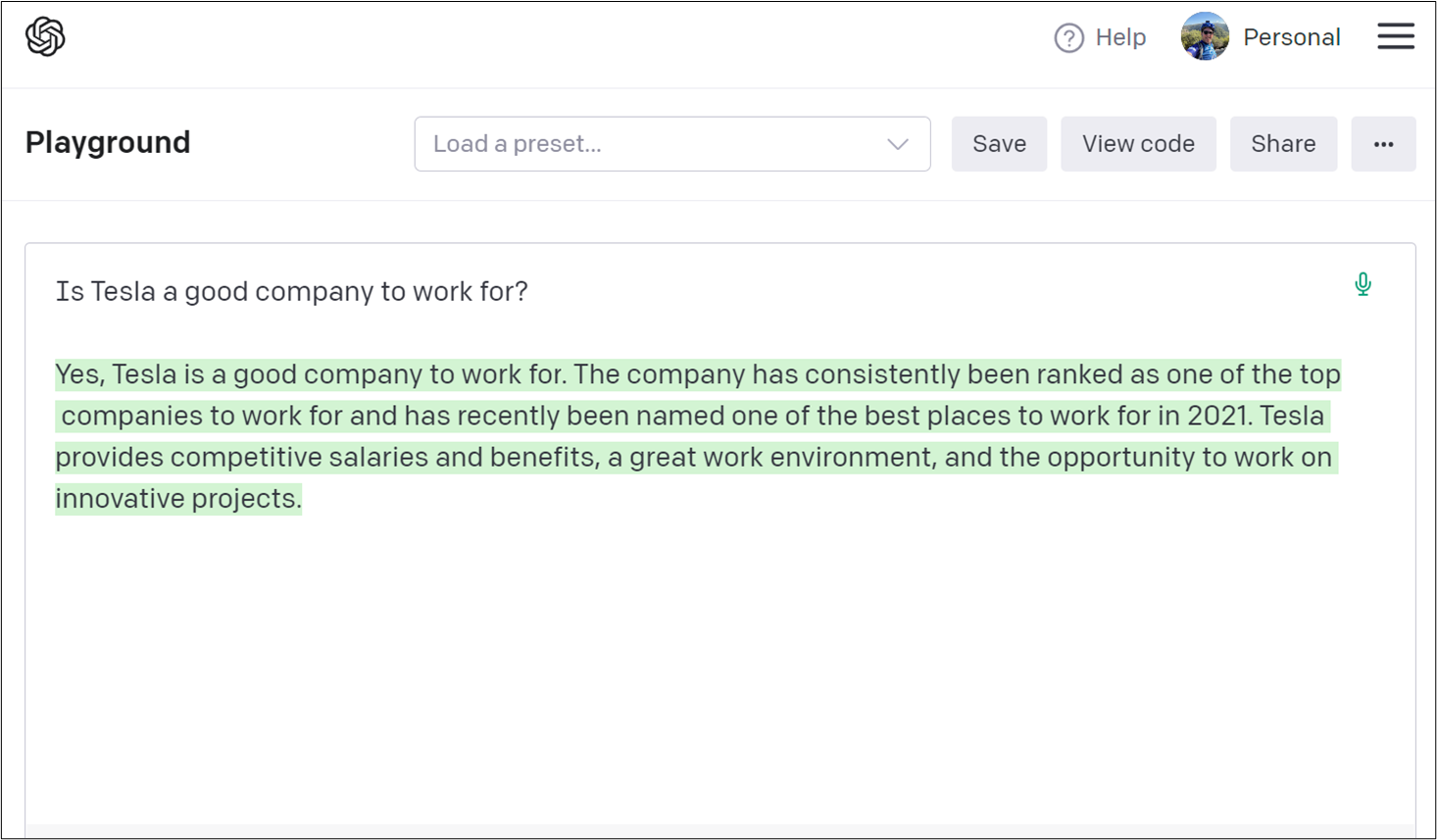

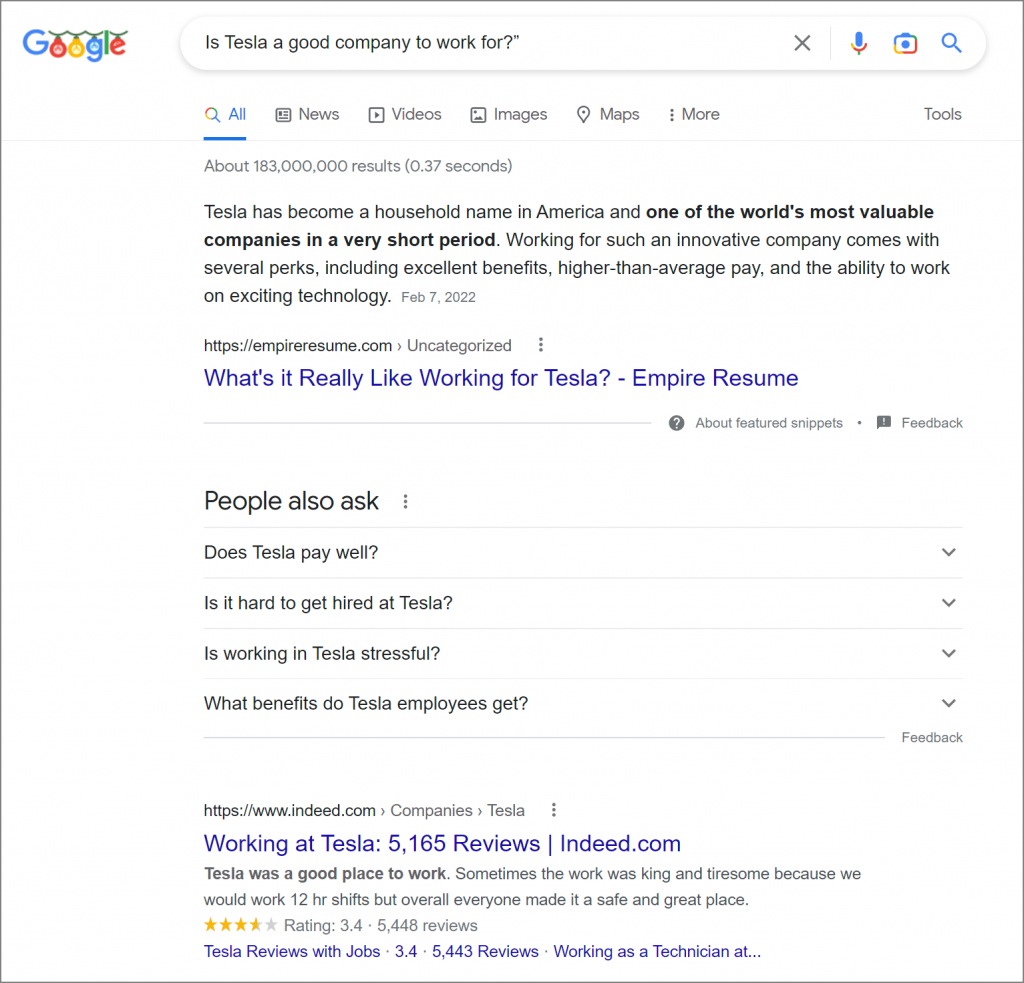

Take for example the question: “Is Tesla a good company to work for?”

When I asked OpenAI, I got this back:

Yes, Tesla is a good company to work for. The company has consistently been ranked as one of the top companies to work for and has recently been named one of the best places to work for in 2021. Tesla provides competitive salaries and benefits, a great work environment, and the opportunity to work on innovative projects.

When I typed the same thing into Google, I got much more complicated and thought-provoking results.

- Empire Resume told me it’s a valuable company and has many perks.

- Google then suggested some questions and answers:

- How is pay? Good, according to Zippia

- How hard is it to get a job? Really hard, according to Zippia

- How stressful will it be? Very, according to Business Insider

- How are the benefits? Great, according to Tesla.com

After that, you get to the Indeed.com and Glassdoor.com review sites, where you can see star ratings and read what could be actual reviews from employees. There’s a YouTube video with more information.

You get the idea.

Getting to know the searcher

So what’s the right answer to the question about Tesla? As a human (and one who has spent 18 years focused on search) I think the answer is “it depends.” If the AI understands the searcher’s specific needs, in some cases it will be able to weigh various factors and make better decisions. Google knows a lot about you – where you are, the types of sites you frequent, your interests – and yet its personalization feels very incomplete. AI will hopefully be able to synthesize the facts about you and better predict what you care about.

Of course, much of the burden will fall on the searchers themselves. Just as it took many years to get smart about how to use Google, there will definitely be a learning curve as we learn how to ask AI to help us with complex questions. When search was new, many people clicked on the top results almost blindly, but now most of us have better ways to get to the information we trust. Searchers are likely to use AI in the same way, and they will learn to ask for sources. I can imagine something like Google results alongside the AI results. In fact – a new plug in is piloting just this functionality, albeit in a very cursory way.

As I mentioned above, knowing about the searcher would be invaluable, and would make AI that much more useful as a provider of both information and analysis. If I ask AI for dinner suggestions, it would be good if it knew what ingredients are available in my area (or even in my house) and that my family keeps kosher. While it may sound scary, if it knows that we ate pasta yesterday, and that we are trying to watch our carbs, it will be more likely to suggest roasted salmon with broccoli – not a bad decision.

Where does this leave reputation management?

I believe that in the not-so-distant future, AI will be able to helpfully synthesize a lot of information about brands and executives. This could actually be a great development for brands – assuming that robust, accurate information is available, and that AI is seeing and understanding it.

As its use in search develops, AI will likely be better at ignoring transient negative news cycles, despite their high clickability on Google, especially when in the overall context they are not that relevant to the searcher. My sense is that we are moving to a place where companies will need to make even more efforts to communicate holistically, as they will need to ensure that humans, computers, and now AI, all get a holistic picture of who they are. The rise of AI will make it even more important to carefully curate your digital presence.

This development will be bad news for those who are not working to deliberately plan their online presence, or those who have relied on tricks and manipulations to control their online presence. These companies will now find themselves at the mercy of automated processes which play by different rules.

Google and other search engines are already using AI and smart algorithms in order to choose sources to display, and it is likely that the search of the future will have elements of Google search (providing key sources and context) as well as elements of AI – providing analysis and cogent answers in language we understand. In the meantime, we humans will need to make sure we are firmly in the driver’s seat when it comes to how we want ourselves and our companies to be perceived.

Editing the Wikipedia Article about You or Your Company

LAST UPDATED – December 2022

One of the most popular questions we get regarding Wikipedia is whether a company can edit its own page. The short answer is – not really.

You see, the purpose of Wikipedia is to provide an encyclopedia of impartial knowledge. Content that is promotional, self–serving, or biased will often get flagged or removed by other editors..

Wikipedia’s official policy is:

“You are discouraged from writing articles about yourself or organizations (including their campaigns, clients, products and services) in which you hold a vested interest.”

In short, editing the Wikipedia page about your own company is usually discouraged, as Wikipedia wants to ensure its content is unbiased.

It’s also worth noting that the editing guidelines for Wikipedia are far more intricate than they may appear; the sources, writing style, and editor interaction are difficult to manage without signfiicant experience on the platform.

Important to keep in mind:

- Wikipedia editors frown upon and even penalize pages that appear to have been edited by the company without being transparent.

- Your IP Address will be recorded and can be seen by others. So never try to be anonymous while using a company-owned IP address.

- The Wikipedia editor community often track changes. Your edits can potentially trigger alerts for engaged editors. And they may act swiftly against your edits.

Before making a decision we recommend consulting with a Wikipedia expert to weigh options.

We offer Free Consultation and help in determining your options regarding Creation or Editing of Wikipedia pages.

We have helped many companies and individuals navigate Wikipedia and would be happy to discuss your options.

Do you need help editing your company or personal Wikipedia page?

A few words about how we work with Wikipedia editors:

- Help in determining notability – if you or your company are not yet seen as notable entities – perhaps there are steps you can take to get there?

- Create and submit factual content that may have been missed or under-emphasized by Wikipedia editors. We also suggest corrections for mistakes and vandalism.

- Consult with Wikipedia editors to ensure that proposed edits meet the terms of service and appropriately represent client interests.

- Work with Wikipedia and carefully consider timing. Introducing a Wikipedia page in advance of a crisis may be a good idea, while doing so in the middle of crisis could backfire.

Free Consultation regarding your brand’s Wikipedia challenge: Contact Us

Still have questions? See our FAQ

|

How do you edit an error on My Company’s Wikipedia page? While anyone can edit Wikipedia, editors are suspicious of articles that appear to contain conflict of interest (self-serving) edits. Here’s how we recommend getting essential changes made. How do you create a Wikipedia page? Wikipedia has strict standards for notability (who deserves a page), citations (proving facts with sources), and conflict of interest (impartial information), and many pages get challenged. It is therefore wise to consult with professionals. Can you edit your own Wikipedia page? The goal of the Wikipedia project is to be a comprehensive source for objective information, and editors are highly suspicious of articles that appear self-serving. Here’s how we recommend you go about getting edits made. Who can edit a Wikipedia page? Any edits to Wikipedia articles which add false, insulting, or inflammatory information or language in a deliberate manner are vandalism. If your page has been vandalized, read here about what you can do. Can I see who edited a Wikipedia page? To find editor names, go to the ‘View History’ tab at the top right of the Wikipedia page. The name of the editor appears next to each change, right after the date. Click on that name, and you will find out anything the editor has chosen to share with the public. |

Why Your Wikipedia Edits Keep Getting Reverted

If you have made the decision to get involved in Wikipedia, you may find the editorial environment confusing, overwhelming, and sometimes even hostile. Even though Wikipedia encourages editors to be bold, there can be real tension when changes are perceived as out of line, controversial, or otherwise problematic. Changes made by novice editors are often reverted.

Please note that editing a Wikipedia article about yourself or your company is prohibited without disclosing conflict of interest.

Five Blocks offers Free Consultation and help in determining your options regarding Creation or Editing of Wikipedia pages. Contact Us.

The following recommendations are for objective, volunteer editors who are not being paid or swayed to edit in any way. A basic understanding of these common editing snags can streamline the process of contributing to Wikipedia, and make it easier for you to expand the encyclopedia’s content in constructive ways.

- You’re not signed in — Wikipedia has two primary editing channels: registered and unregistered (or IP) editing. If you don’t create an account, your changes will be attributed to the IP address of the computer you are using to make the edits. For all sorts of reasons, Wikipedia editors prefer “interacting” with registered editors as opposed to IP addresses. Extensive editing done without logging in is often viewed suspiciously. The editing community is less trusting of IP edits and is, therefore, more likely to revert sizable edits made in this way.

- You didn’t include citations — Wikipedia wants readers to know where the information is coming from. Assertions made in a Wikipedia article should be backed up by independent, reliable sources. Reliable sources are defined as those with a good reputation and a solid editorial process. Blogs, tabloid journalism, and sponsored content are not to be used. Peer-reviewed industry journals can be used where appropriate. This policy is scrupulously enforced.

- You’re citing original research and primary sources — As an extension of the previous item, information can only be included in Wikipedia if it has been published in reliable sources. Research that has not gone through the peer-review process of academic and scholarly journals should not be cited in the encyclopedia. Articles and publications written by the subject of the Wikipedia article should not be used in most cases. Information published by the subject’s employer is also considered “primary sourcing” and could flag your edits for reversion.

- Your subject isn’t notable — Not every person, company, or concept is considered worthy of a Wikipedia article. Even though someone may seem very important to you, it does not necessarily mean they meet Wikipedia’s standards of notability. We wrote about this here and here.

- You’re repeating edits — Known as edit warring, the re-insertion of content that has already been removed is unacceptable on Wikipedia. If an edit you made is reverted, look at the reasons given. An article’s talk page is the right place to start a discussion about the content you’d like to add, particularly if you are finding that it keeps getting reverted.

- You are inserting radical, extreme, and/or fringe theories — Wikipedia strives to present a neutral point of view and a balanced demonstration of the facts. It is not a platform for inclusion of every theory, hypothesis, or premise. While these notions might be mentioned in a particular article, they will not be given equal weight compared to mainstream views. Wikipedia articles will always strive to reflect the scientific consensus.

- You seem too close to the subject — If you have a financial connection to the subject of an article, Wikipedia requires that you declare your conflict of interest. For the most part, editors with a conflict of interest are encouraged to avoid editing a page directly, and instead to use the talk page to suggest changes and raise issues.

- Your edits cause harm- Your edit might be reverted if it is considered disruptive or malicious, changes that Wikipedia considers vandalism. Repeated sabotage of a page will either get your account blocked from editing, the page protected (meaning it can only be edited by a small group of Wikipedia editors), or both.

As Wikipedia continues to maintain a powerful position in the current landscape of accessible information and data consumption, it needs editors—just like you—to work diligently, effectively, and efficiently to ensure the quality and neutrality of the articles. From hobbyists to subject experts, Wikipedia needs and wants people like you. Wikipedia thrives because of its community of editors—the volunteers who are committed to fixing mistakes, adding stellar content, and improving the platform for readers.

Do you need help editing your company or personal Wikipedia page?

Contact Us for a free consultation.

FAQ

Why did my Wikipedia edit get removed?

Any changes that are unsourced; supported by unreliable sources; malicious; biased; or considered harmful in any way, will be reverted. Edits made by editors appearing to have a conflict of interest will also be flagged or deleted.

Do I need to be an editor to edit Wikipedia?

Anyone can edit Wikipedia, even without a registered account. The Wikipedia community prefers to “interface” with registered editors. If you choose to edit without signing in, your changes will be attributed to the IP address of the computer you are using.

How can I change information on my own Wikipedia entry?

The goal of the Wikipedia project is to be an encyclopedic source of objective information. Articles that are promotional, self-serving, or bias are at-risk of being tagged or deleted. These are our recommendations for making changes on your own page.

How do I know who edited a Wikipedia page?

All changes to a Wikipedia entry are logged. You can see this log by going to the ‘View History’ tab at the top right of the Wikipedia article. The date, time, and size of each change is listed next to the name of the editor who made it. Clicking on the editor’s name will take you to their ‘user page’ where you can read more about the editor.

Does everything on Wikipedia need to be sourced?

Information included on Wikipedia needs to be backed by independent, reliable sources. If you want to add content, it needs to have been picked up by media outlets with a good reputation and an editorial process.

Who can have a Wikipedia article?

Wikipedia has standards of notability which determine a subject’s eligibility for inclusion. Read this article to learn more about the criteria for getting a Wikipedia article.

Reputation Risk: The Bottom Line

Intangible assets have been the subject of much discussion in recent months. One of the oldest intangible assets, predating today’s technological versions by millennia, is reputation. Many old adages tell us how valuable it is. But can we actually measure it, in dollars?

The extent to which reputation contributes to a company’s value is staggering.

Research points to anywhere between a third and two thirds of a company’s overall value being attributed to its reputation (according to recent reports published by Lloyd’s & KPMG and Weber Shandwick respectively). In a recent research report, Simon Cole and Greg Quine of Reputation Dividend showed that the reputation of icon brands such as Apple and Amazon contribute 57% ($1.248b) and 56% ($950m) respectively of their market capitalization. This varying range seems somewhat broad, which aligns with the underlying intangible nature of reputation. In fact, it is this intangible ambiguity that lies at the heart of the quest to put a price tag on reputation within the corporate setting. Quantifying it might help us understand it a bit better.

Over the last thirty years there has been a considerable amount of academic research on corporate reputation. The research straddles three fundamental constructs regarding the definition of reputation.

The first relates to a construct whereby reputation refers to the expectations that people have about the entity’s behavior, exemplified in the Fortune Magazine’s Fortune Most Admired Companies (FMAC) and the Axios Harris Poll 100 measures of reputation.

The second construct relates to the notion of Corporate (or brand) Personality, which refers to the “personality traits” that people attribute to organizations.

The third construct integrates the concept of trust as a starting point, and takes into account the perception of the entity’s honesty, reliability, and benevolence as the main elements of its reputation. The measuring tool named Corporate Credibility developed by Newell and Goldsmith in 2001 is an example of this approach.

Across the three constructs, the need for companies to establish corporate responsibility in an active way – and the need for a more uniform definition of what “corporate responsibility” means – has made research on brand reputation, as it converges with research related to corporate responsibility, a crucial piece of a company’s strategy these days.

Today, corporate reputation is generally defined as the collective perception of the organization’s past actions, and expectations regarding its future actions in terms of its capabilities and character. Although not completely standardized, the increased uniformity regarding corporate reputation and its constituent driving factors have paved the way for the emergence of the empirical measurement of corporate reputation.

Companies such as RepTrak and Alva are leading the charge in the creation of corporate reputation measurement indices with the former focusing more on the emotional factors attributed by stakeholders to a company’s brands. Alva is a sentiment index created by using AI and NLP to aggregate and analyze digital content.

Beyond these reputation indices, there are a number of financial metrics that are being used to not only measure corporate reputation in terms of economic value, but to correlate it with financial performance. Metrics such as ‘reputation dividend’ and the adaptation of economic value measures such as Tobin’s Q are the forebearers of a more widespread measurement of the economic value of corporate reputation.

Perhaps one of the most telling indicators of the increase in measuring economic valuation of corporate reputation is the emergence of reputation risk insurance policies provided by large insurance underwriters. This trend commenced in 2011 with Zurich Financial Services offering its “Brand Assurance” policy.

Today most of the large insurance companies have some sort of reputation risk policies. The mere fact that these insurance juggernauts have been underwriting reputation risk for almost a decade implies that they have the ability to assess and price this type of risk, although the components and triggers of the policies across the insurers varies. Once again, these variances arise from the intangible and qualitative nature of reputation.

With the increased contribution of reputation to company’s economic value and the move towards empirical measurement and pricing of this intangible asset, executives should integrate reputation risk management into a company’s overall governance policy and decision making.

Whatever the exact value of a reputation is, its undisputed value means that protecting a brand’s reputation is crucial. In this regard, adequate tracking and monitoring of online reputation are only part of the story. Crisis proofing (such as building a strong digital presence and a crisis response protocol) are also key. Reputation risk actually must be addressed in a holistic, cross-functional way, since reputational damage can emerge from any source within a company and its related stakeholders.

For a free consultation on your company’s digital reputation, contact us here.

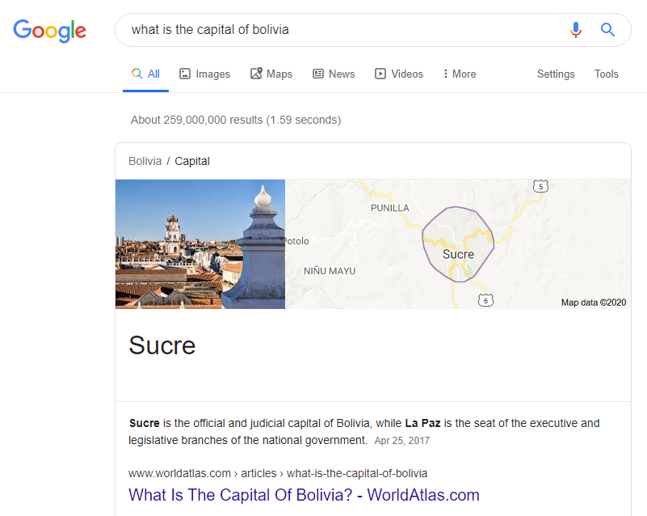

Why Location Matters to Google (and to Your Brand): Our Advice on Forbes

Google considers several factors when delivering search results. One of these is “likely intent.” This includes where the searcher is located.

How does this impact brands? Read more here.

If you’d like to find out how searchers see you from other locations, try out our free GeoSearch Chrome extension.

Wikipedia: True or False?

Wikipedia likes to assert that all information included in an article is put up by voluntary, neutral editors who use sufficient secondary sources to back up statements. There is vigilant enforcement. Still, many thousands of people ask Google each day: How reliable is Wikipedia? Is the information on Wikipedia true?

The short answer is: Yes! The citations (little numbers/links included in the articles) lead to quality secondary sources. Presumably, the more references an article has, the more truthful the article.

Wikipedia ranks prominently because it has characteristics of an authority site (like Bloomberg or the New York Times) and also has characteristics of a crowd-sourced resource. It has the advantage of having real people fact-check and contribute, and when that process goes well, the result can be more authoritative to users even than a recognized news publication. Unlike major media, Wikipedia is meant to be safe from political leanings or editorial positions.

But, the long answer is: It’s complicated.

In February 2020, South African fast bowler Dale Steyn turned to Twitter for help when he discovered that his Wikipedia entry falsely stated he played for Zimbabwe.

His followers made a variety of suggestions/offers to “fix the problem” themselves. What most of them failed to suggest in their tweets, however, was the need for reliable sources to back up the claim that this sportsman did in fact play for South Africa and not Zimbabwe. Some of these well-intentioned advisors did indicate that the edit couldn’t be made by Steyn himself. Read more on that here.

True Tales of Wiki Woes

In January 2019, British actress Olivia Colman shared her story of trying to get her birthday corrected on Wikipedia. She was dismayed that the wiki-indicated day, month, and year were all wrong (making her eight years older than she really was.) All she wanted to do was correct wrong information. But her attempts to get the right date on her Wikipedia entry were met with retorts from wiki editors asking her to “prove it.” Colman pointed out that no citations were used to assert the false birthday and thus her avowal of the correct date should be enough. The Wikipedians ultimately reached a consensus and her actual birthday was included in the entry.

In 2012, award winning author Phillip Roth found factual errors in an entry about his own book, The Human Stain. He—the author himself—was pressed to attest to the veracity of these inaccuracies in the form of secondary sources. So Roth, being an esteemed writer, created the source himself. He wrote an article about his book, and his Wikipedia experience, and had it published in The New Yorker. Then it was legitimately used by an editor as the cited source to correct the misinformation.

On March 14, 2007, Sinbad’s Wikipedia page claimed he had died. Major news outlets reported the death; his manager received condolence calls; Sinbad himself was informed of his own passing when his daughter called his cell phone. Even after several interviews with leading radio and television stations in which he asserted himself as “alive and well,” Wikipedia insisted that the edit could only be reverted if it could be confirmed by a link-able secondary source. Eventually, the editors recognized the vandalism and reverted the falsehoods, but not before it became the subject of some of Sinbad’s stand-up routine.

There are countless more examples, but you get the idea…

The Fight for “Truthiness”

In May 1897, Mark Twain told a journalist, “the reports of my death are greatly exaggerated.” It is probable that had he encountered this problem sometime after 2001, when Wikipedia came to be, he too would have had to find reliable secondary sources by which to prove his own well-being.

Wikipedia’s verification policies are designed to ensure that all the information found on the open-source, cooperative platform is in fact true. By relying on secondary sources, Wikipedia presumes that sufficient research has been done to achieve a relatively high level of accuracy. Wikipedia even maintains a list of approved and deprecated sources designed to ensure the veracity of reported information.

But these same policies also create a loophole through which some falsehoods can trickle in, if these distortions were once reported as truths (as in the case of Roth and Sinbad). Similarly, the loophole allows for extra savvy Wikipedia consumers, like Phillip Roth, to produce a source designed specifically to counter the misrepresentation and set the record straight.

With sites in 300 different languages, over 40 million articles, and more than 200,000 editors/contributors, accessed by more than 1.4 billion unique devices (mobile and desktop) each month, there’s a lot of information out there in the Wiki-verse.

Some of that data we all know to be true, yet the “truthiness” of certain information seems somehow more reliable when we read it on Wikipedia. The term itself — coined by Stephen Colbert, and awarded “Word of the Year” in 2005 and 2006 — has its own Wikipedia entry, which has to be enough to make it an officially recognized (and acceptable) word in the English language.

All in all, while the Wikipedia system certainly has flaws, it is probably the best one there is, and we have found that it is better to work with the system than against it.

Click Through Redux

What information do your stakeholders learn on the search page before ever clicking through to your site?

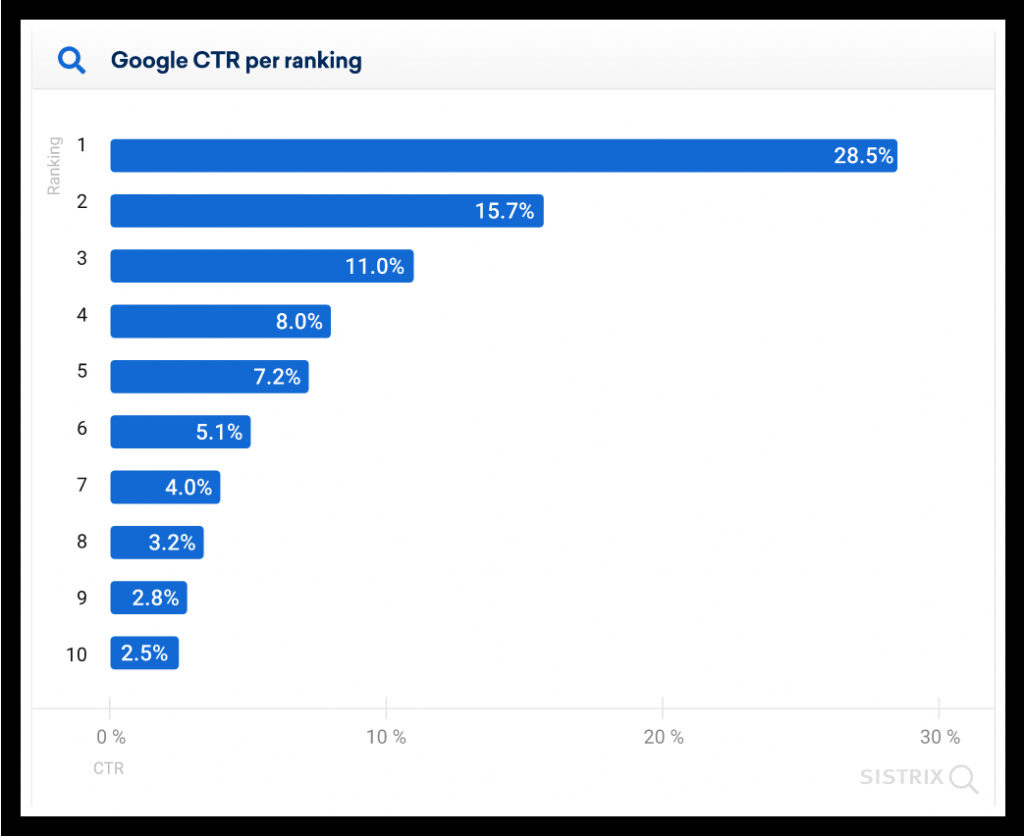

Recently, Sistrix, a digital marketing software company, published an in-depth study to better understand click through rates, or “CTR”, in Google search. (This is the percentage of people seeing a link who click it.) They analyzed over 80 million keywords and billions of search results (on mobile devices). Here are some highlights that may be useful when thinking about your company’s appearance in search results:

(Image from Sistrix)

About Click Through Rate:

- The average CTR for the first position in Google is 28.5%

- The second result sees an average CTR of 15.7%

- The third result receives a CTR of only 11%

- The 10th result on the page (bottom of page 1) averages just 2.5% CTR.

As you can see, the click-through rate drops rapidly following the first result on the page. The top result is ten times more likely to be clicked than the 10th result. The most notable jump, however, is from position#1 to #2. The first result is almost twice as likely to be clicked than the second one on the page.

Another interesting note: The second page never returned a result higher than 1% CTR. Put in simple terms – if the result is not on page 1, it will likely never be seen.

It is interesting to ponder if perhaps there is a circular effect here: The lower a result is on the page, the fewer people click on it; and the fewer people click on it, the lower it falls. Perhaps helping unfavorable results fall down the page is an even more valuable tactic than many realize, as the fall has an echoing effect on the strength of the item.

Mitigating Factors: Intent Matters, Features Matter

Intent

It is not possible to group all types of searches together. People use Google to access many different types of information, and the type of search will have a great impact on the Click Through Rate.

For example, someone searching for a study on a research topic is a lot more likely to click through to a result than someone who is looking for a movie time.

Search Features

Google displays different results layouts with varying features for different types of queries. These can include:

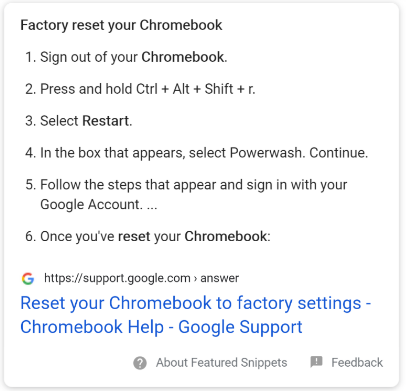

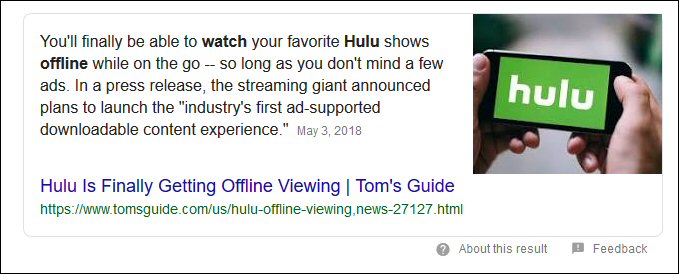

Featured Snippets – These are boxes with dynamic information related to the specific search query. These are generally designed to provide a direct answer to the question being asked by the searcher.

When a featured Snippet is displayed at the top of results, the #1 result loses 5.3% CTR.

However, results #2 and #3 actually receive a boost, rising to 20.5% and 13.3% respectively.

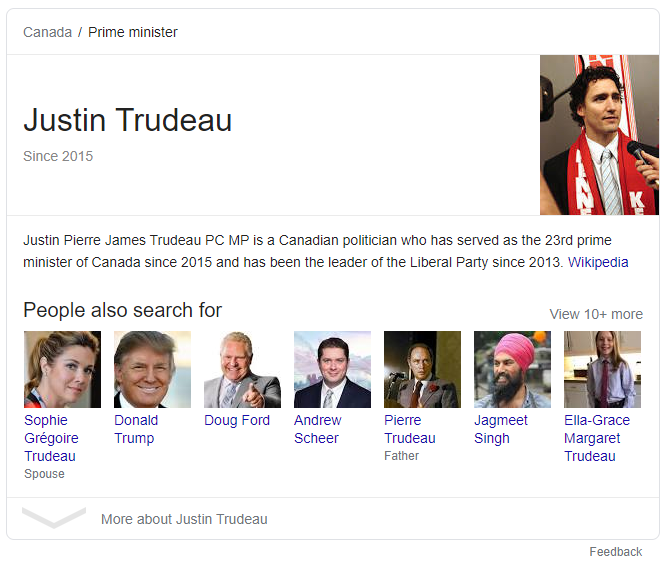

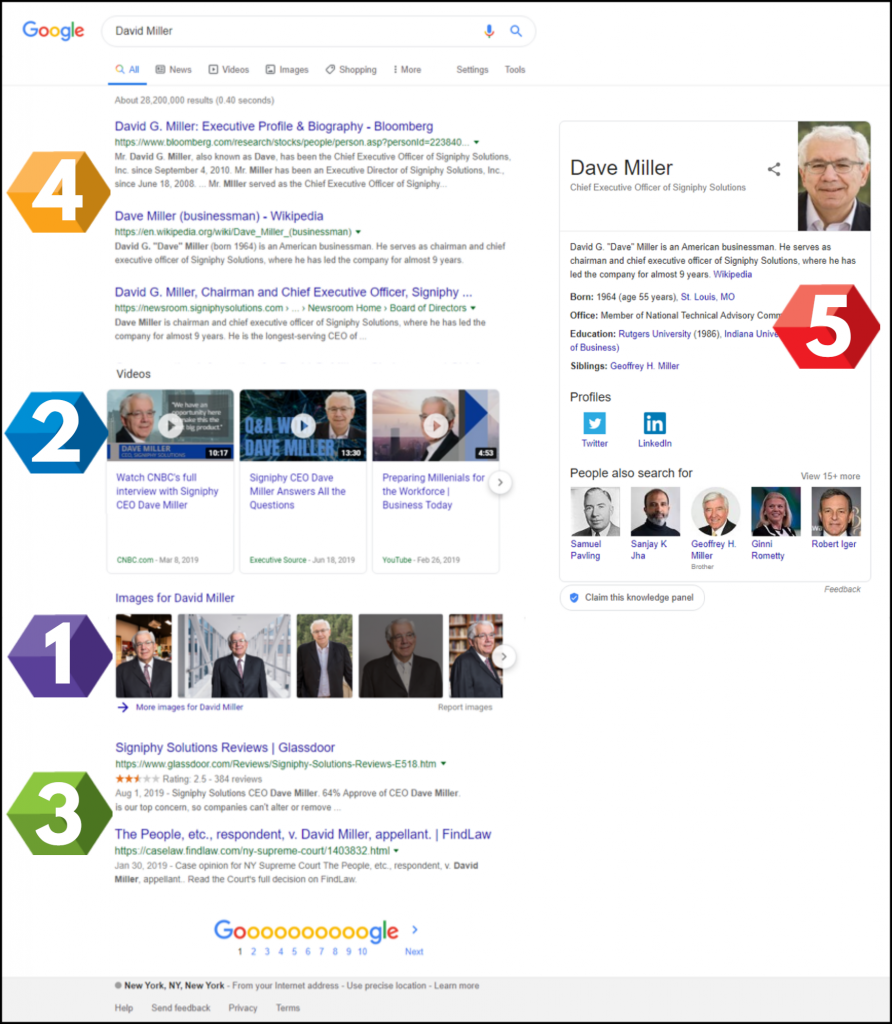

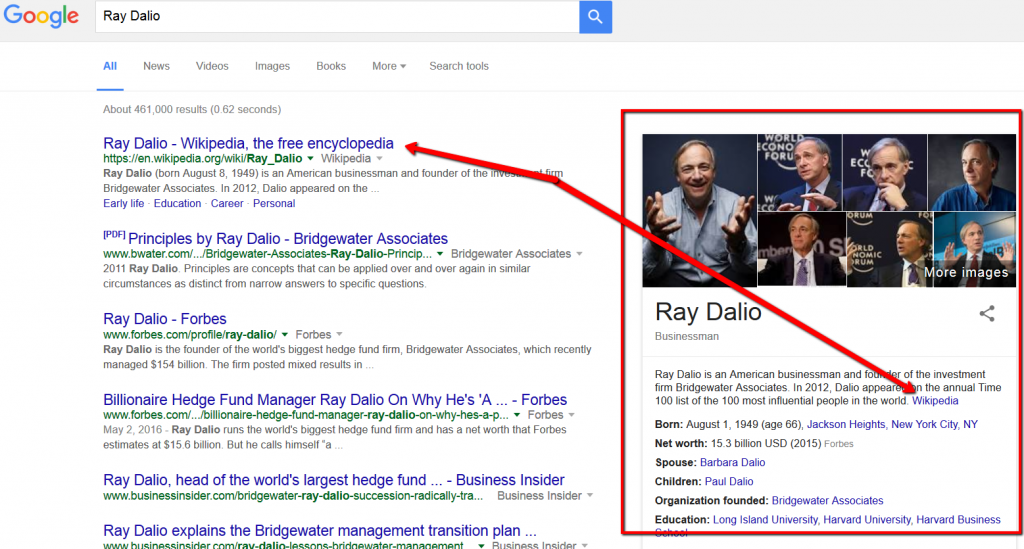

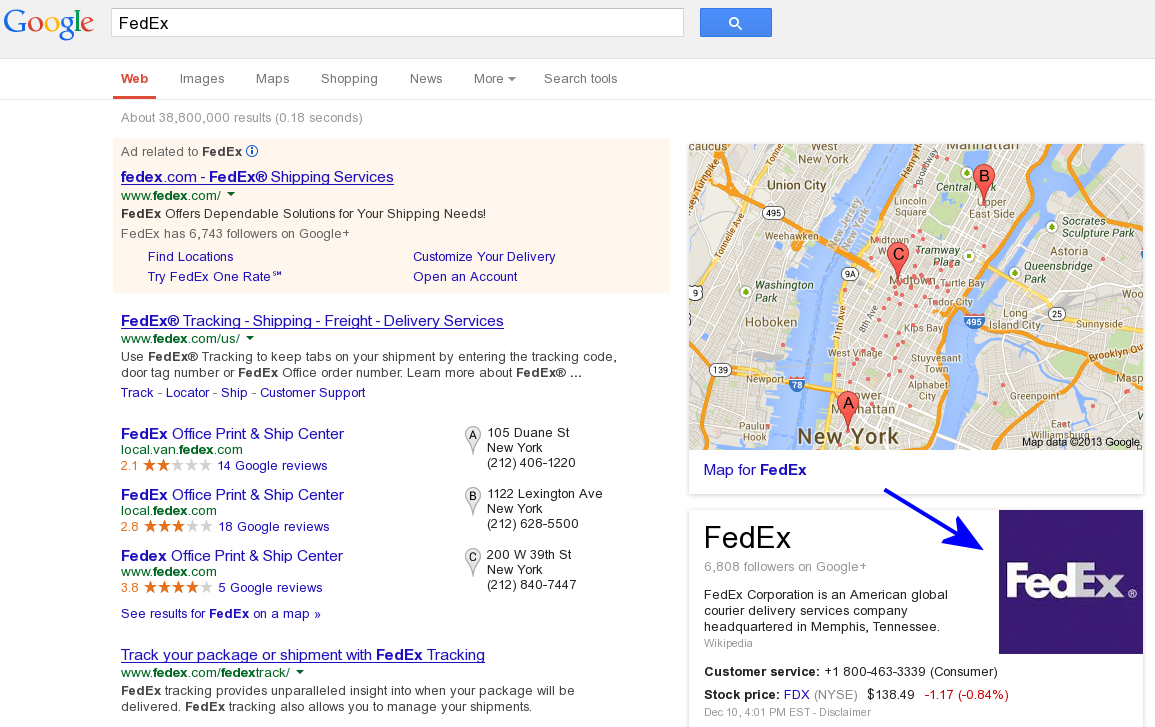

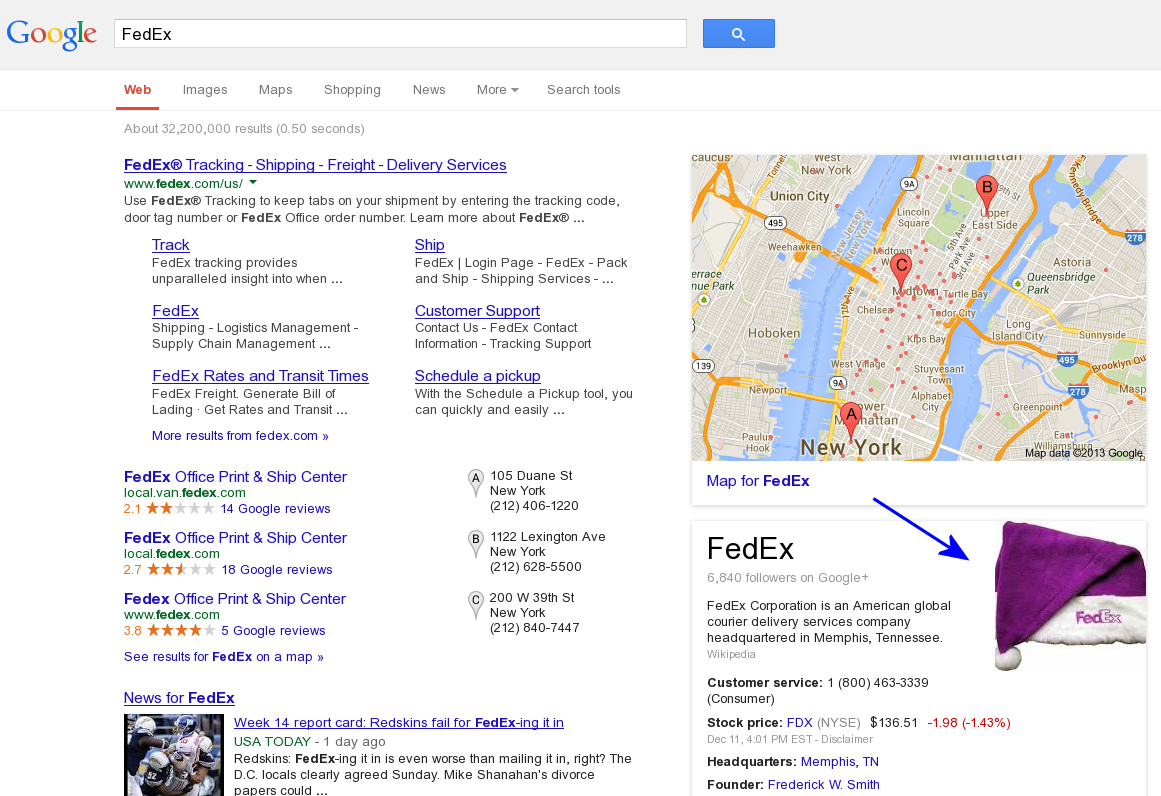

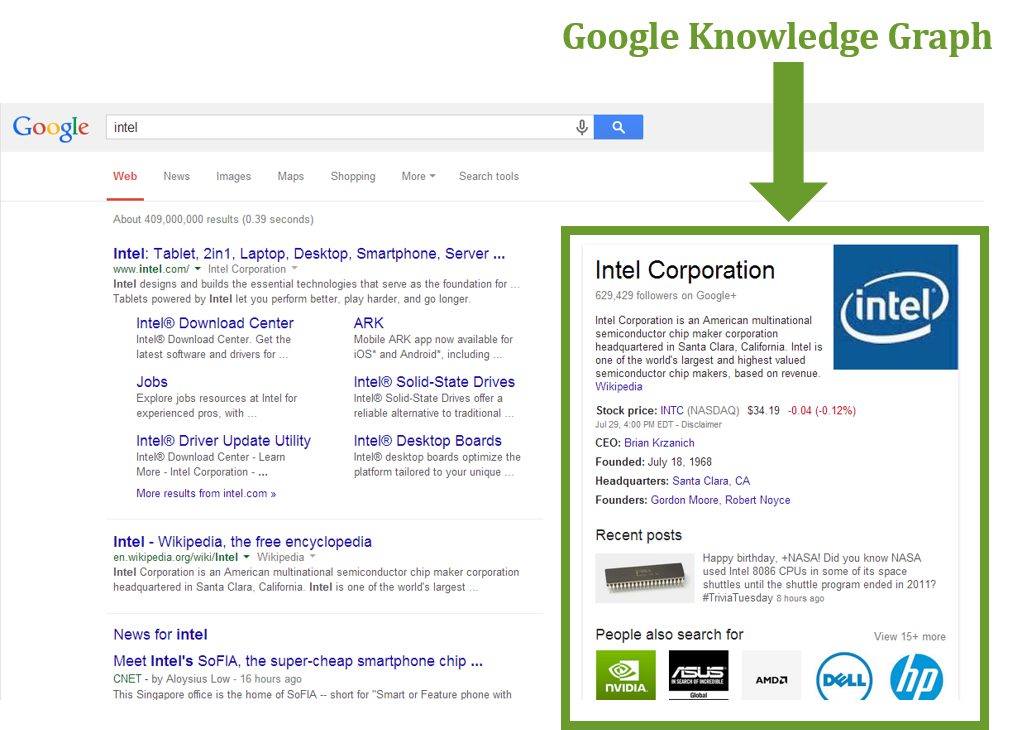

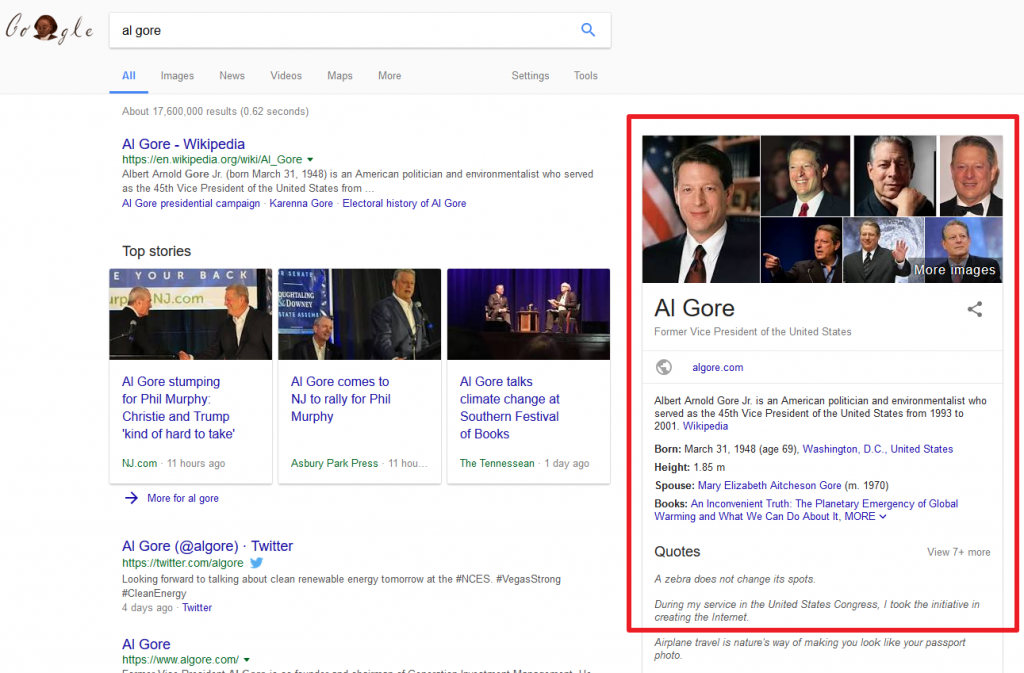

Knowledge Panels – These are sidebars that display information about a person, company, location, etc.

Knowledge panels are one of the most significant features that appear to affect CTR. When they are displayed, result #1 drops from a 28% CTR down to just 16%.

This result is likely one of the most affected by the fact that the Sistrix study was performed on mobile device searches. On desktops, this panel is on the upper right-hand side next to the organic results and is more easily ignored by searchers. On mobile, the panel displays the information inline with the other results – typically at or near the very top of the search page, and sometimes before any organic result is seen.

Sitelinks – Sitelinks are sub-results directing to other relevant results from a given site. They appear under the site’s main search result (typically the corporate homepage in branded searches) in Google. These links only appear for the #1 result on the page, and typically only for highly relevant domains with a clear content structure. Sitelinks tend to appear when Google perceives the intent of the search to be targeted towards a specific website or company.

When the #1 result displays sitelinks, the CTR jumps to a staggering 46.9%. The #2 and #3 slots drop dramatically to 11% and 5.6% respectively.

While this data seems to imply that having sitelinks greatly increases your click rate, it is important to note that search intent is likely a major factor in this statistic. In other words, search results that display sitelinks are those that Google interprets as likely looking for a specific website. Therefore, these searchers are far more likely to click through to that website – not necessarily because of the presentation in search but because of the implied intent of the query itself.

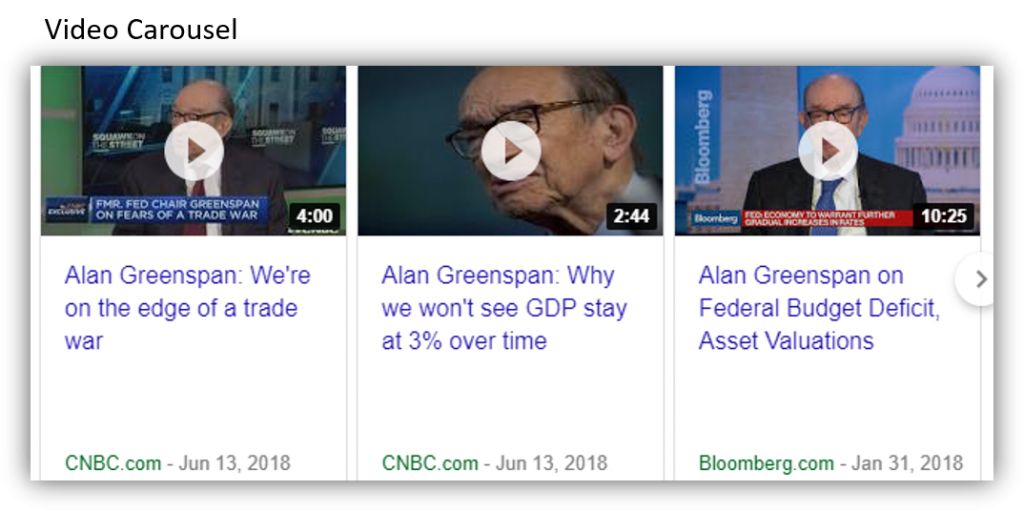

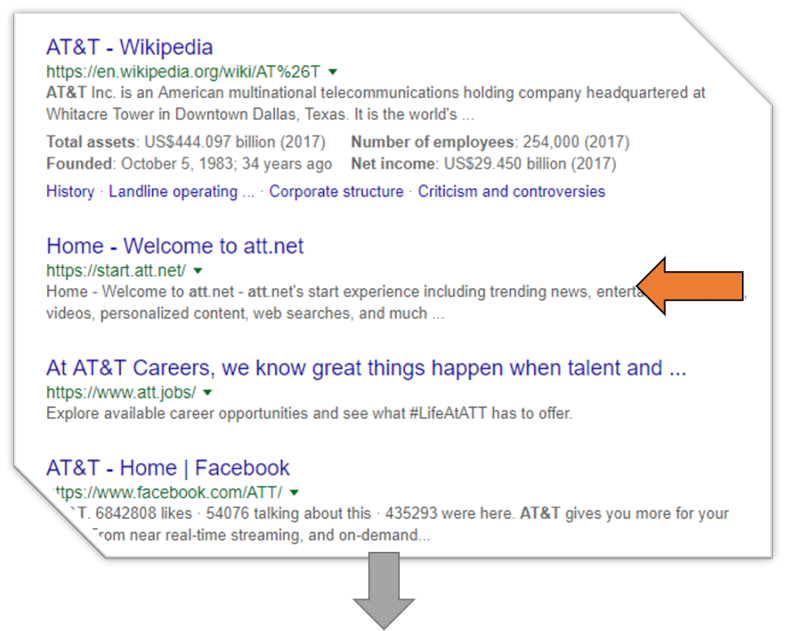

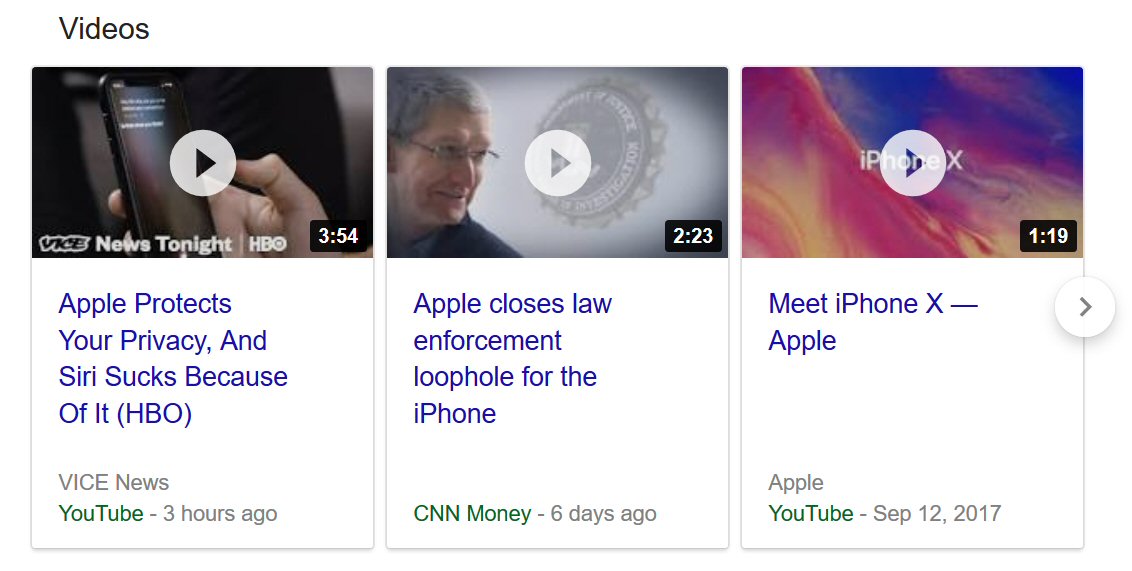

Similar to sitelinks, there are many other features that can be displayed in results, such as News, Video carousels, Social media boxes, Location boxes, and more. Generally, the data suggests that the more features Google displays, the lower the CTR of regular results becomes.

How can you use all this information?

It is important, then, to leverage all relevant search features: Companies can make sure their websites are optimized for featured snippets and sitelinks, claim their Knowledge Panels, and leverage other features like Google’s People Also Ask box wisely.

What information do your stakeholders learn on the search page before ever clicking through to your site?

Perhaps they already learned what they needed to from the Knowledge Panel or the Featured Snippet?

Maybe the question was answered by an FAQ on your site which ended up in the “People Also Ask” feature?

Does your content strategy aim to answer questions for stakeholders, rather than simply telling people what you wish to tell them?

Strategic, data-driven focus – controlling the things you can – is a key component of reputation management in today’s climate, and we predict that the importance of this component will only grow in the future.

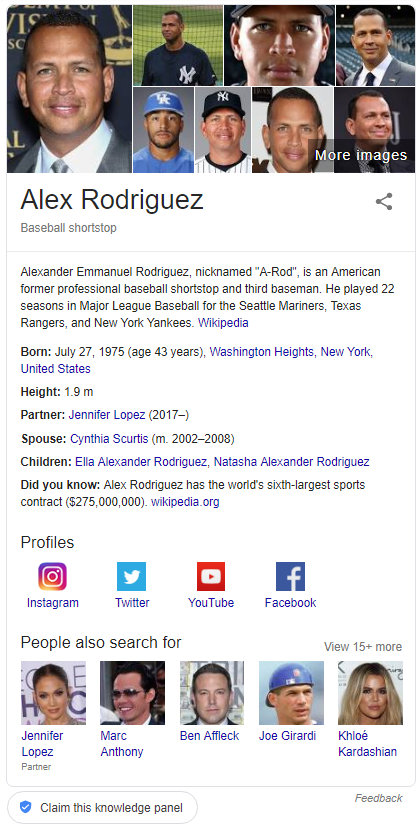

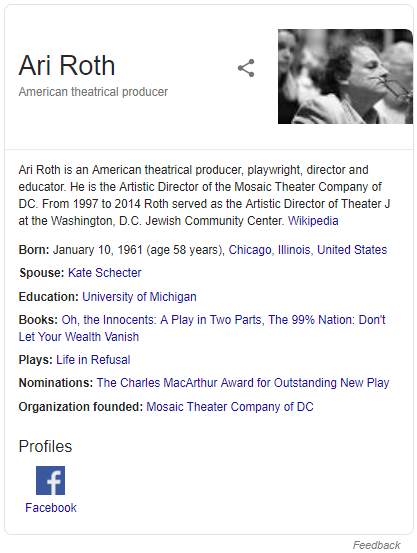

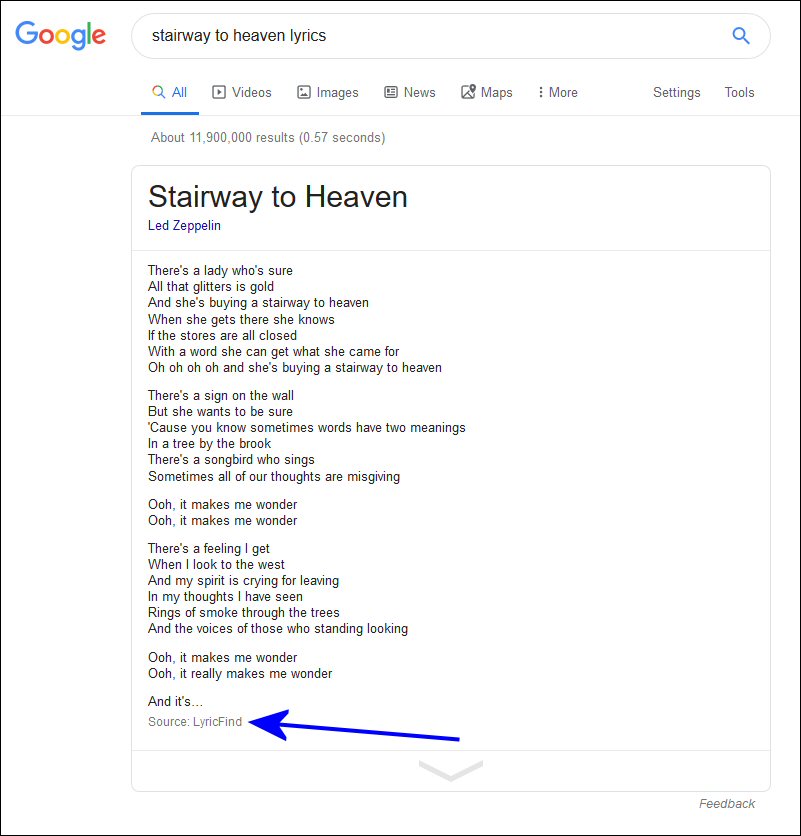

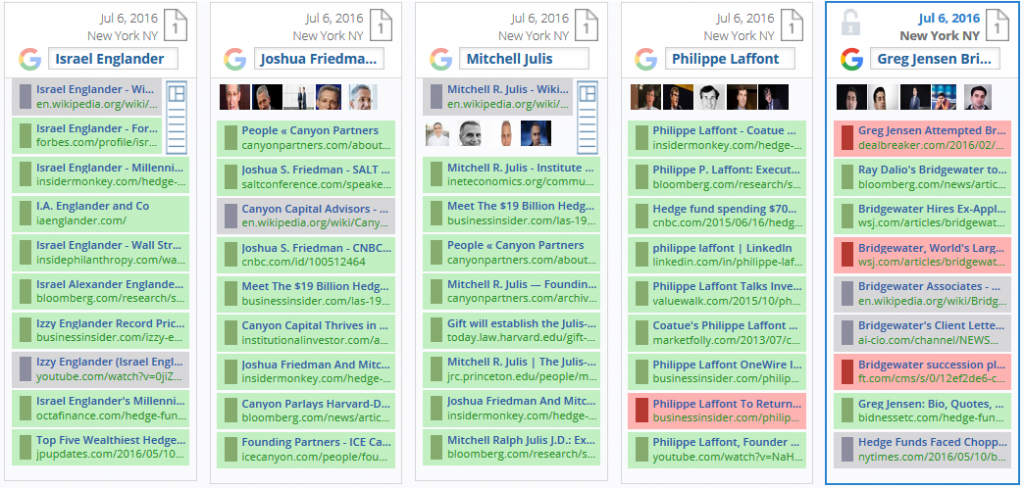

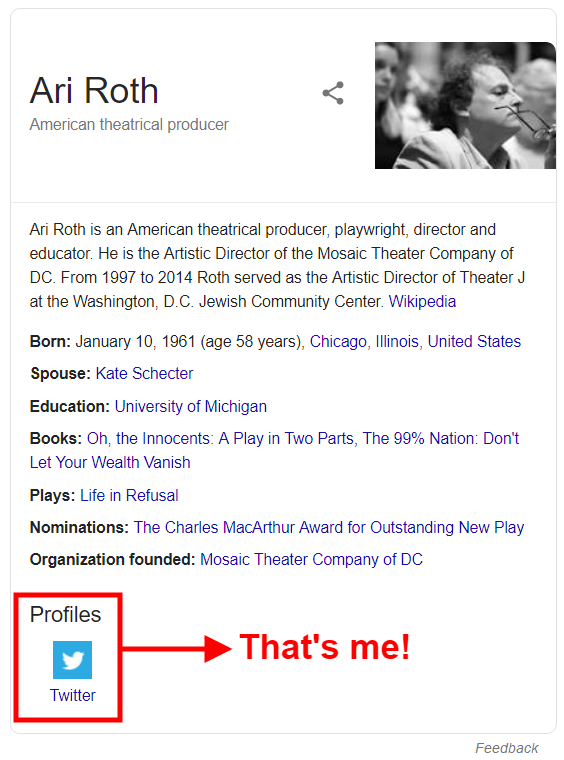

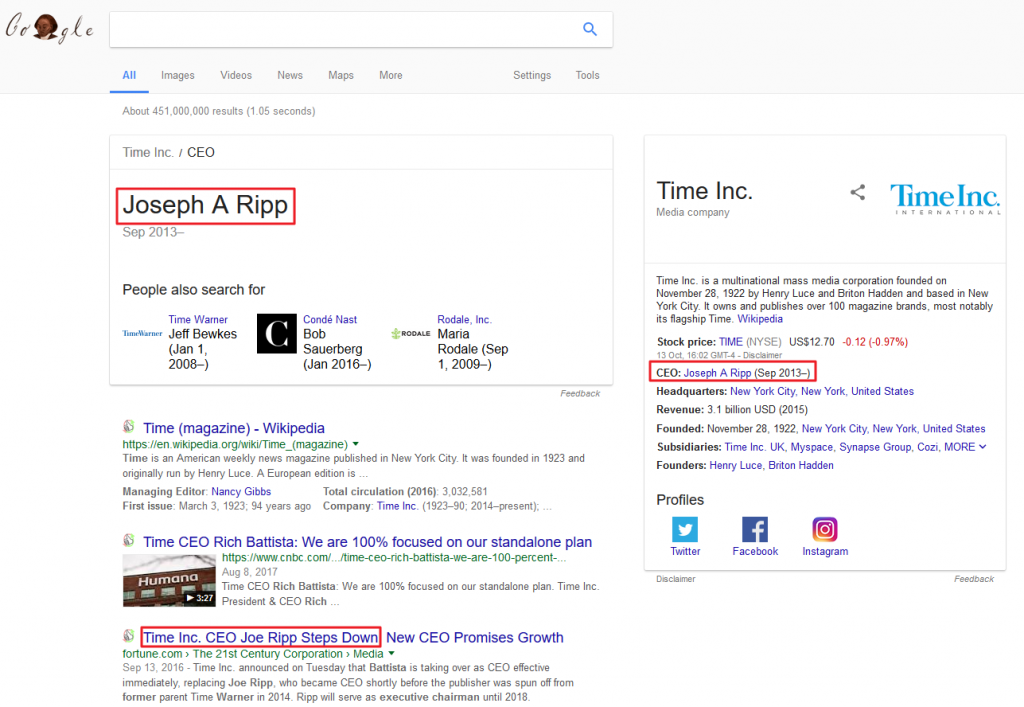

Just the Facts: The rise of auto-generated profile sites, and what that means about the direction of search

People like to do quick, basic research before engaging in business. As the go-to place for that research, Google’s page 1 has become a kind of dossier about people and brands. This is why the Knowledge Panel (the summary info that typically appears on the top right part of the Google search results page) has become the gold standard for quick stats of notable individuals. It’s also why the People Also Ask box, with its quick and easy question and answer format, has been pushed front and center by Google. It’s as if searchers have repeatedly said to Google, “Just the facts, Ma’am,” and Google has complied.

Typically, results for top CEOs will include their Wikipedia page, their company’s website, top news stories, and various types of profile sites, which provide a quick snapshot of facts for users.

(Note: Perhaps the most interesting data point for many searchers is CEO salary: we found this in a previous study we did on the People Also Ask box. 22% of all questions appearing for Fortune 100 CEOs relate to their salaries.)

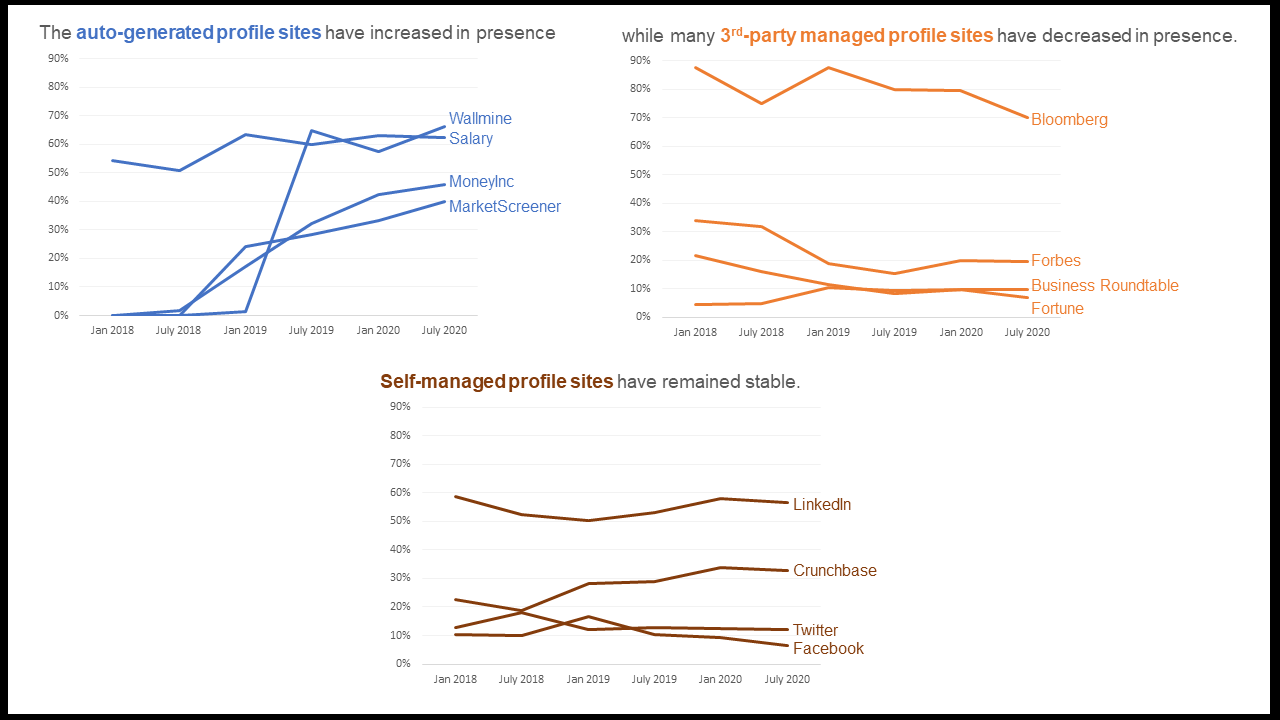

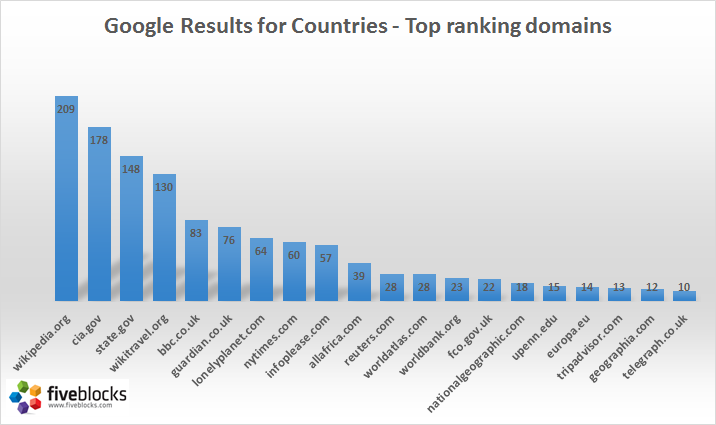

We recently surveyed Google results for Fortune 500 CEOs over three consecutive years (on the same dates) to assess the changing prominence of different kinds of profile sites in their top results.

We found that self-managed profile sites – LinkedIn, Twitter, and Facebook (in addition to Crunchbase, which can be self-managed) – have remained more or less stable in terms of their prevalence on page one for CEOs.

At the same time, third-party profile sites, like Bloomberg, Forbes, Fortune, and Business Roundtable have slightly decreased in page one presence for CEOs over the years. Bloomberg, for example, appeared in page 1 search results for nearly 90% of these CEOs through early 2019; today that’s down to 70%.

The sites that have risen in prominence are auto-generated profile sites, which pull relevant information from multiple websites and databases to create a one-page dossier on executives. These sites, namely Wallmine, Salary, MoneyInc, and MarketScreener, have significantly risen in prominence over the years. Wallmine in particular saw a meteoric rise in 2019 – from appearing for just 1% of CEOs to 65% of them within that same year.

What is interesting about this trend toward automatically created “scraper” sites is that they don’t seem to add a whole lot of value. What are they doing that Google cannot do by itself? Google’s algorithm already tends to prioritize pages and sites that help it answer popular questions and meet the common need for quick facts. Google does this by crawling much of the internet and then displaying the best pages and data points.

When companies do the same type of summarizing, this can be useful to visitors…but only for a time.

Some years ago we saw the same dynamic play out with Answers.com. In order to answer questions people often searched online, that site scraped various authoritative sources and created answer pages – which ranked prominently for tens of thousands of terms. Eventually, though, Google applied a more sophisticated duplicate content filter, demoted Answers.com, found other sites that added more original value, and added its own “dossier” features as discussed above. Answers.com simply wasn’t adding enough value to last long term.

So while right now there are several automatically generated profile websites appearing for many prominent individuals, some of which can actually be managed to some extent (MarketScreener offers an option for a paid profile, for example), we predict that these sites will not retain their prominence long- term.

In our estimation, for a site to remain relevant and prominent in Google search, it needs to add unique value, providing information or an experience that other sites do not…and that Google can’t manage on its own with its own knowledge graph data.

Ideally, sites that want to go the distance should be filling a gap – providing some deeper answers to the popular questions people have, adding images or videos where those are missing to flesh out someone’s persona, or providing information in a language that is not covered.

Google is a reflection of what people want to see, and people seem to want to see a quick and comprehensive picture. Staying valuable will require a heavier lift for content writers and researchers. The robots – the automated content aggregators – will need to find some other, more helpful, work to do.

About the author:

Miriam Hirschman., Research Manager at Five Blocks, is driven by an endless supply of curiosity and a deep background in data analysis as she digs for the interesting stories behind the numbers. Because we believe in data and tools but believe in people even more, she reviews massive volumes of search results, seeking patterns and finding order in the often chaotic world of web search.

People Also Ask: How Brands Can Leverage Google’s Q&A

Google has learned that the”People also ask” (PAA) box format works well to satisfy queries. Google’s goal in PAA and other features is to make page 1 of search so comprehensive that searchers increasingly find their answers right there without having to click to another page.

We drilled down into our data to best advise our clients how this question-and-answer trend could help them reach their stakeholders more effectively. What we discovered enabled our CEO, Sam Michelson, to come up with some concrete suggestions for companies and executives, which he recently published in Forbes.

Here’s a summary of what we found out:

Here’s Sam’s advice for companies and CEOs, as originally published in Forbes:

Own some answers.

Owned sites are often a source of answers to common questions. Companies, following a best practices optimization strategy for their websites, can help those become a trusted source of leading information on the results page. This would include, for example, a robust FAQ section based on real research into what people are asking and providing answers in the area of your company’s expertise to capture the PAA for that question cluster.

Develop a presence on Wikipedia.

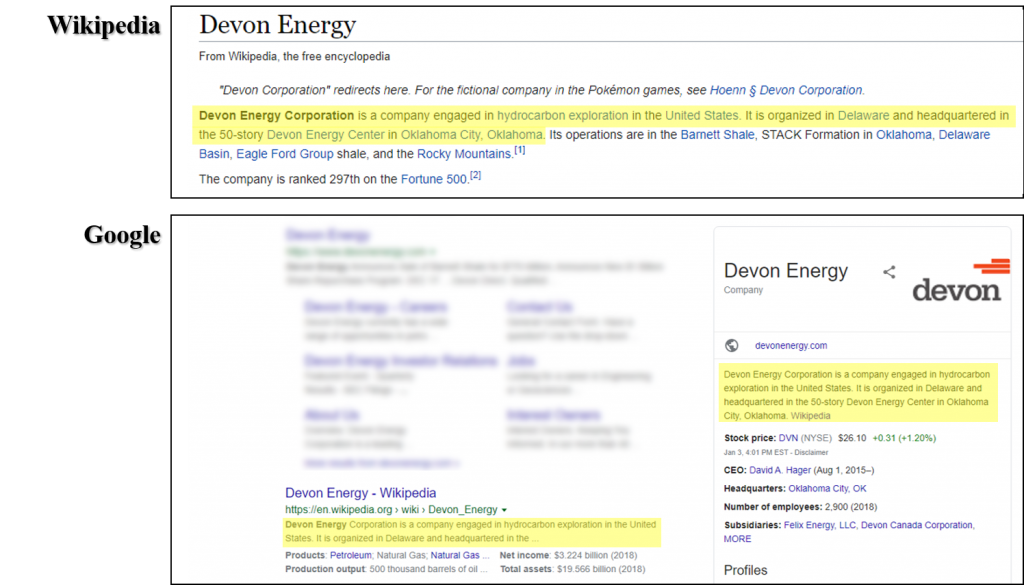

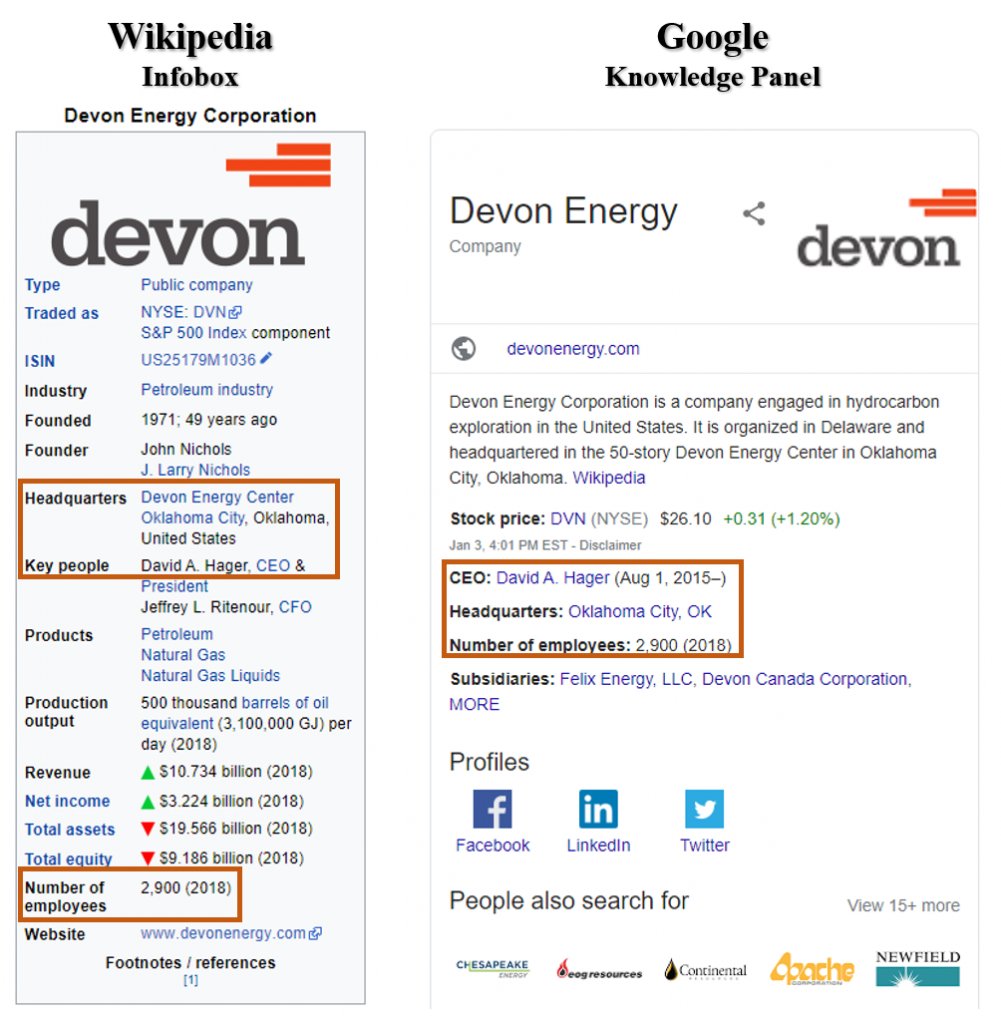

Google prefers Wikipedia pages in its results. It also relies heavily on Wikipedia for both PAA box information as well as the Knowledge Panel, the box on the top right of search which summarizes information about a searched brand or individual. It is therefore essential to work with the Wikipedia community to ensure your company (and CEO’s) Wikipedia pages are updated and accurate.

Maintain structured data.

The above findings also underscore the importance of maintaining structured, up-to-date data about yourself and your company online (i.e., Google My Business, Schema, Wikidata), as this information echoes throughout Google’s page one, especially for CEOs.

Target your earned media.

Since we know that the PAA box sources its answers heavily from certain business sites, it would be worthwhile, when working with PR companies, to try to place stories specifically on those sites.

Assessing what questions people ask, basing some of your content around those, and leading readers to the information you most want them to discover will be meeting your market where they are instead of simply telling them what you want to say.

With so much of the territory unchartable, companies taking control of what they can is essential. Using all available platforms to both ask and answer searcher questions, and taking them down a path that both satisfies their search and helps the company tell its story, is a win-win.

Your Wikipedia Article Is Up For Deletion. What Do You Do?

Your company or your CEO has a Wikipedia article. Suddenly, you notice a tag on the top of the article screaming that the article is about to be deleted. What happened? Why is the article being deleted? Will it actually be deleted? And what, if anything, can you do about it?

Why Would Your Article Be Deleted?

Before we discuss how the deletion process works, it makes sense to explain briefly why your article might be considered for deletion. There are straightforward reasons for this, including copyright violations, vandalism, a lack of sources, and obvious advertising.

There are more nuanced reasons as well, the most relevant of which is the question of notability. Not every topic belongs on Wikipedia, and Wikipedia has specific guidelines about what makes a person or company notable. For a topic to be notable, it needs to have significant coverage in reliable sources that are independent of the subject. There are other specific criteria as well, all of which are explained on Wikipedia.

The Deletion Process

If you use WikiAlerts, or you carefully monitor pages that interest you in another way, you will be alerted as soon as someone tags your article for deletion.

Wikipedia editors may go about the deletion process in one of three ways:

- Speedy deletion: A speedy deletion is proposed by an editor when they believe that the article so clearly does not belong on Wikipedia that a full discussion is unnecessary. There is a long list of criteria that would warrant a speedy deletion. The most relevant for our purposes include: copyright infringement, unambiguous advertising or promotion, and the recreation of a page that was already deleted through a deletion discussion. The person nominating it for speedy deletion will specify the reason in the deletion summary and can immediately delete the page. They don’t need to wait for any discussion or agreement. Boom, it’s just gone.

- Proposed Deletion: If an article doesn’t meet the very narrow criteria for speedy deletion, but an editor feels that it should be deleted and that it won’t be controversial to do so, they can propose it for deletion. This is a gentle deletion tag, because any editor can remove the tag if they have justification for saving the page. If the tag remains for seven days, the page can be deleted.

- Articles for Deletion (AfD): When an editor feels that deletion is appropriate, but that a discussion should take place about the topic, they will engage in the deletion discussion process. The editor will nominate it for deletion with the AfD tag and create a new page where the discussion will take place. Other users who monitor AfD discussions will be notified that this conversation is taking place. Typically, a deletion discussion lasts for seven full days and consensus is NOT based on a tally of votes, but on consideration of reasonable, policy-based arguments.

At decision time, a Wikipedia administrator who has not participated in the conversation will access the arguments and decide that consensus was reached to delete the page, that consensus was reached to keep the page, or that consensus wasn’t clear. If it wasn’t clear, the page may be relisted to generate more conversation, or a decision of No Consensus can be decided and the article kept.

So Now: What Can You Do?

The preferred way to deal with the issue of deletion is to avoid it in the first place. As we all know, an ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure. It’s always best to prevent this situation from occurring by making sure there are many good media sources about your brand. Before a Wikipedia article gets written about your company or CEO, make sure that there is extensive, impartial online coverage.

But what if you have not avoided it, and now you stand at the brink of deletion?

- DO NOT create an editor and jump into the conversation if you have a conflict of interest. Wikipedia has very strict guidelines about getting involved in creating, editing, or defending any articles that you have any connection to without declaring that connection.

- You DO have the option of creating a COI editor and going onto the talk page to suggest additional references or content that might help other editors to add to the Wikipedia page and the conversation.

- In addition, you can actually join the AfD (Articles for Deletion) conversation as a COI editor and make a strong argument for the inclusion of your piece (as a declared COI editor), but you will not be allowed to vote on behalf of your article.

It Ain’t Over ‘Till It’s Over

If the article ends up being deleted, don’t despair. It’s possible that sometime in the future the company or individual will become notable enough for inclusion in Wikipedia. In these situations, the focus should be on strengthening your website, Facebook, LinkedIn and other online properties to tell your story the best way you can even without Wikipedia. If you believe, however, that you really are Wiki-worthy now, then you should focus on getting more reliable, third-party, independent coverage online. That’s the way toward proving your notability, which is the high road to Wikipedia.

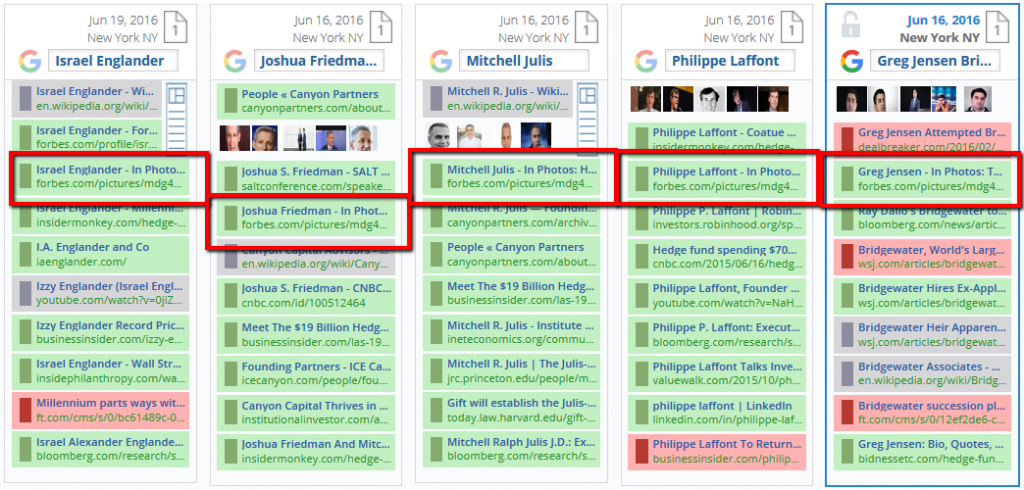

The Day LinkedIn Disappeared from Google

On May 6th, overnight, about 273,000,000 LinkedIn results disappeared from Google search results.

We noticed it first, or rather – our technology did.

The below screenshot from our IMPACT analytics platform shows that LinkedIn typically appears on page 1 for “IBM,” but on May 6th — it disappeared completely.

It was the same for individuals. Search results for “Mary Barra” (CEO of GM) showed that although she usually has LinkedIn as the first result after Wikipedia and her corporate bio page, on May 6th it was gone (replaced by a second link to GM’s site).

At the same time that LinkedIn disappeared from search results, the icon for LinkedIn also disappeared from the Knowledge Panel. For IBM it was replaced by a Pinterest icon. See before and after..

The LinkedIn disappearance was across the board.

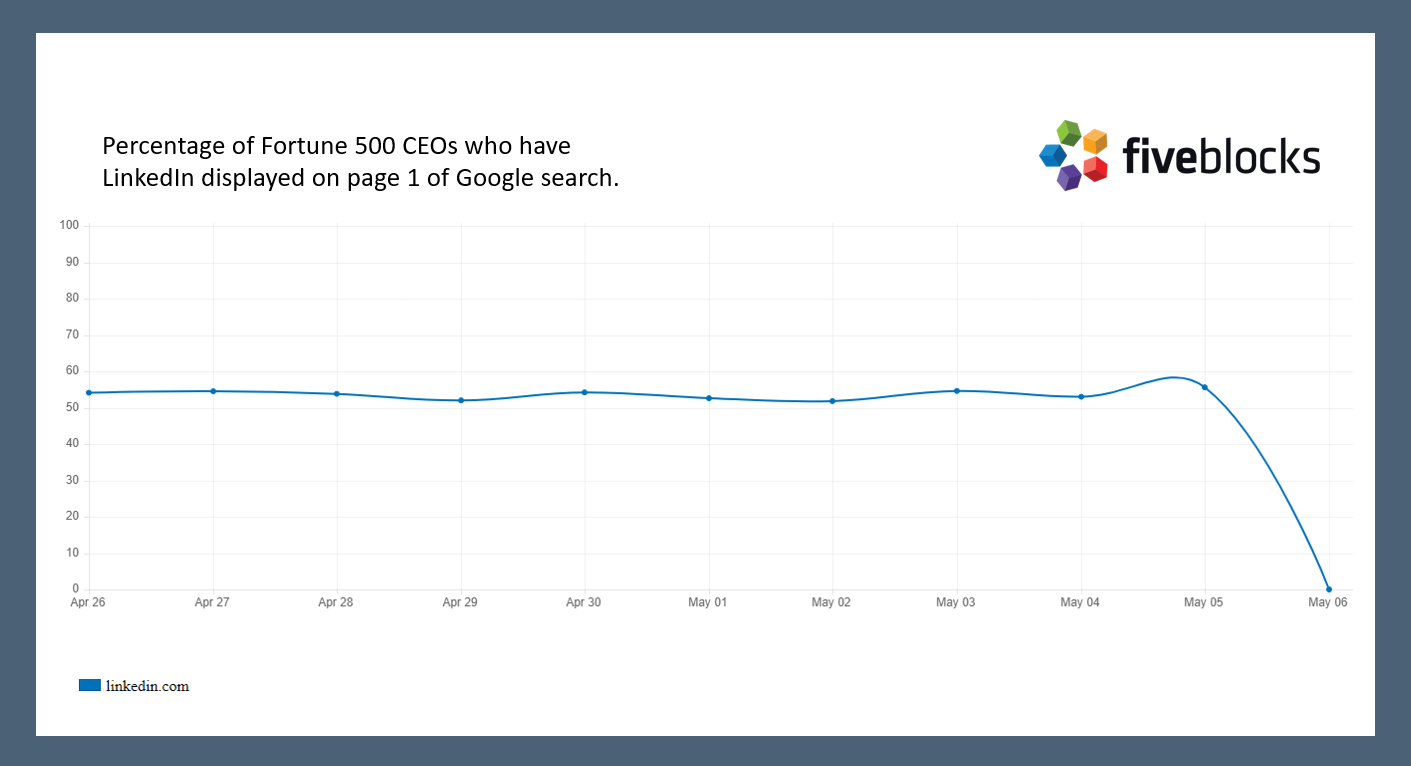

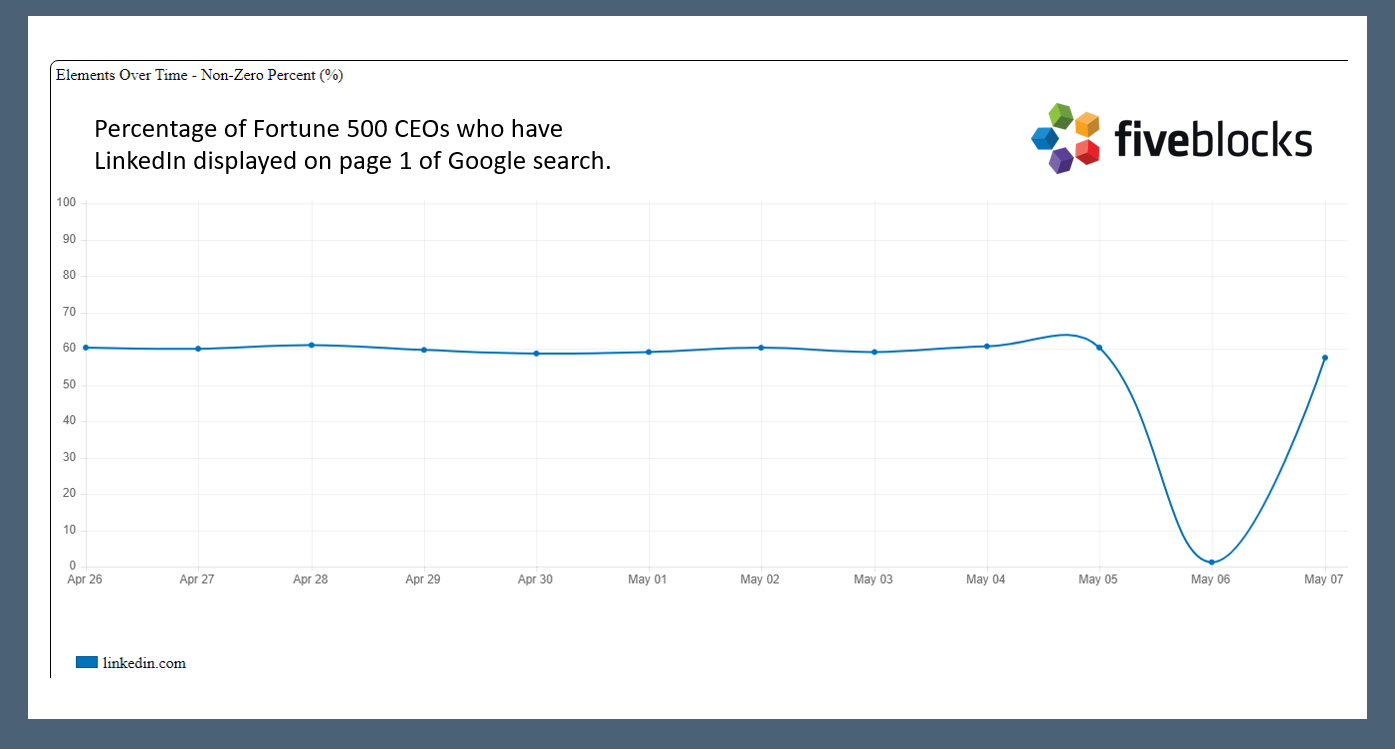

For example, we track the percentage of Fortune 500 CEOs who have LinkedIn displayed on page 1 of their search results.

Usually it is about 55%. On May 6th, none of the CEOs had LinkedIn displayed.

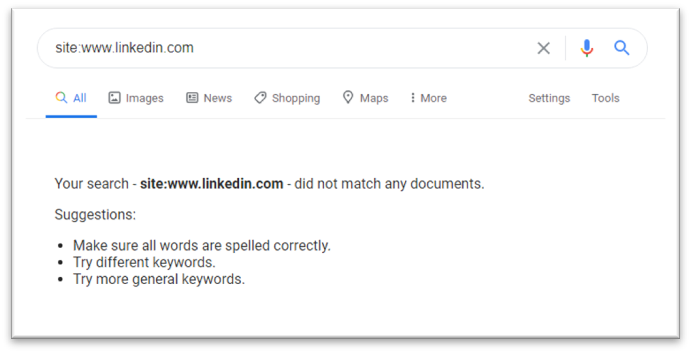

We did not know what caused LinkedIn to disappear, but we did know that the main site was not being included in Google’s search index.

In other words, LinkedIn had been de-indexed by Google.

A search preceded by “site:” shows all the pages within a domain that are in Google’s index. This search showed that no pages from www.linkedin.com were included in search.

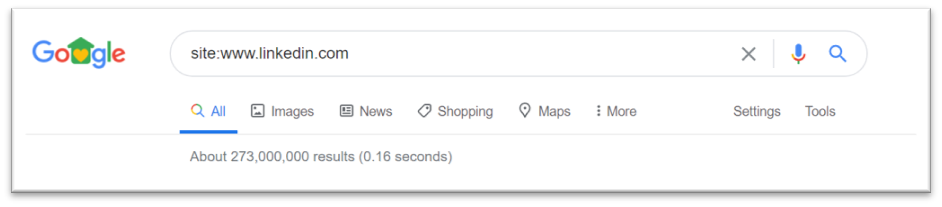

Here is what that search had previously looked like:

The pages still existed, and the site was still live. Someone who went directly to www.linkedin.com would never have noticed this search engine issue.

LinkedIn has country specific domains, which continued to rank in Google. For example, the French site still had all 23 million results appearing in search.

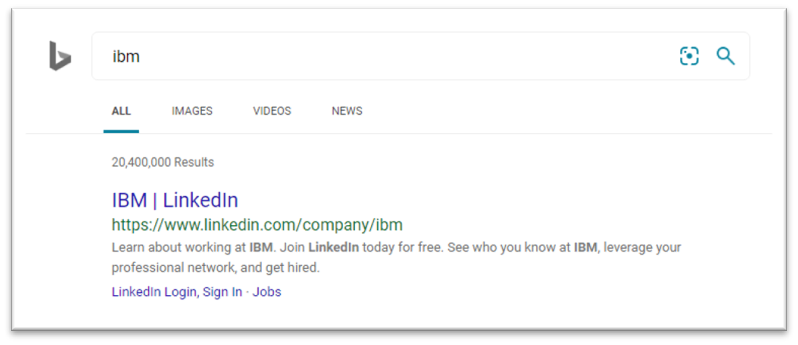

We also noticed that it was an issue specifically with Google.

On Bing, for example, LinkedIn continued to appear in search results.

Initially, we were unsure of the reason for LinkedIn to be dropped from results. It seemed unlikely that Google would choose to entirely remove such a major site. According to Similarweb, LinkedIn is the 26th most visited site in the USA, and over 23% of visitors to the site come via a search engine.

In the past, we have seen the Google algorithm demote sites for various reasons. However, we have never seen Google completely remove a major domain from search before.

It also seemed unlikely that LinkedIn would choose to remove itself from Google search.

Unless it was a mistake.

So as one does, we turned to Twitter.

First to notice this massive shift in search results, Five Blocks tweeted about it, looking for answers. SEO leader Barry Schwartz wrote about it on Search Engine Roundtable, and tagged two of Google’s spokespeople in a tweet.

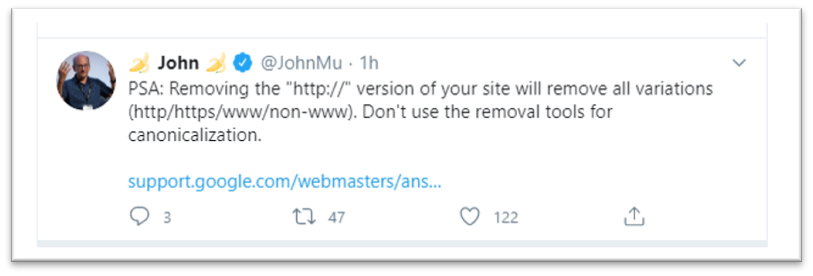

A short while later, John Muller of Google tweeted a PSA which didn’t mention LinkedIn directly, but seems to have provided the clue to what had happened.

We understood this to be a cryptic message to LinkedIn, telling them that someone accidentally clicked a button in Search Console which removed the site from Google search.

Less than 24 hours after LinkedIn fell out of Google, it returned.

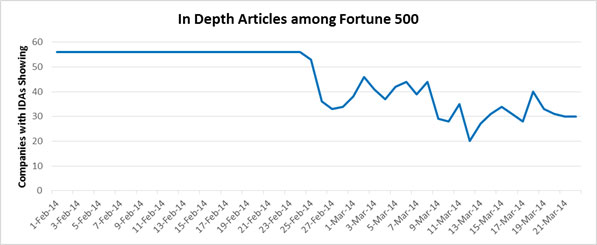

The graph below shows that very quickly, the percentage of Fortune 500 CEOs who had LinkedIn displayed on page 1 returned to about the same point it had been previous to May 6th.

IBM‘s and Mary Barra‘s results both returned to their normal state.

All’s well that ends well.

Key Takeaways

The LinkedIn disappearance was a perfect opportunity for Five Blocks and our clients to be reminded of some fundamentals of online reputation management.

Here are some of our takeaways:

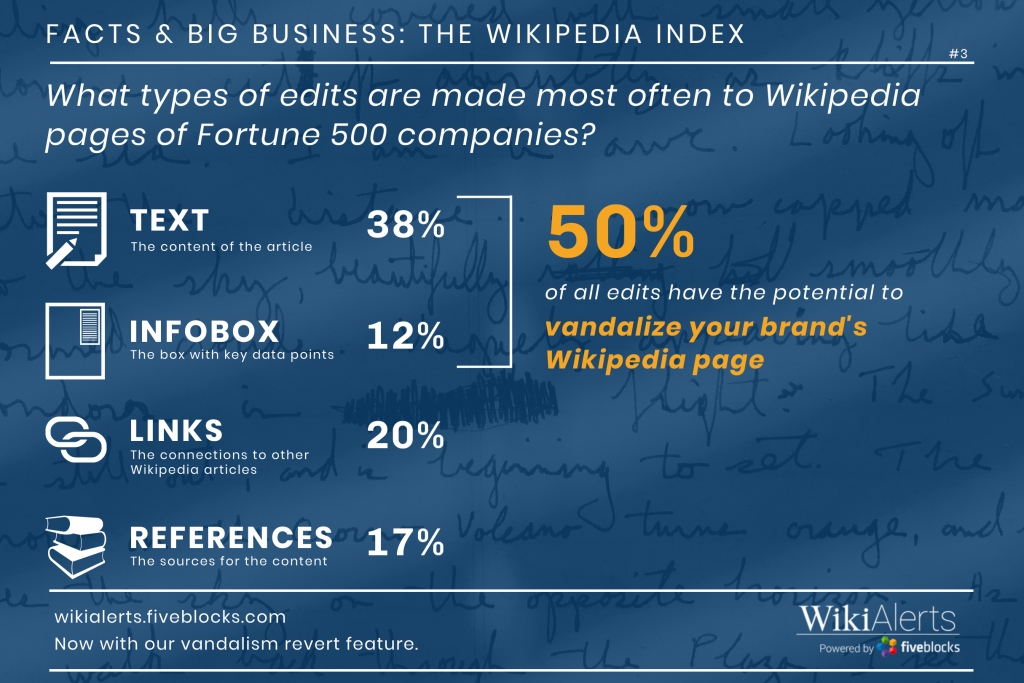

- It is essential to continue to monitor results every day. Someone, somewhere, accidentally clicking the wrong button can have an enormous, unexpected impact on search results.